Cutting to the Core: Finding the Meta-narrative

Cutting to the Core: Finding the Metanarrative

Citizen Kane

“You are not your job! You are not your bank account! The things you own end up owning you.” – Fight Club

“I guess it’s hard for people who are so used to things the way they are—even if they’re bad—to change. Cause they kind of give up. And when they do, everybody kind of loses.” – Pay it Forward

“The will is everything. If you make yourself more than just a man, if you devote yourself to an ideal, you become something else entirely.” – Batman Begins

“With great power comes great responsibility.” – Spider-Man

“War is a sin, but sometimes, a necessary one.” – Elizabeth

Although no one will use the word “worship” for the narrative altars our society sacrifices on—the multiplex, their living room, and the comic book store—our entertainment venues have become our sanctuaries, and storytellers our preachers. This isn’t new; even Jesus taught with parables—a tale that conveyed truth. At the end of the day, every storyteller attempts something similar, though the reasons vary. Some hope to convey a particular truism; others want to spin a yarn based on something they wrestle with. Maybe they only wish “to tell a good story,” yet still this preaches to us, as by that very notion they interpret what makes a good story: their worldview invariably seeps through. Even if they’re just out for cheap direct-to-DVD dollars, they’re going to give the audience what they think it wants, which is expressing a worldview all the same.

“Strange, isn’t it? Each man’s life touches so many other lives. When he isn’t around, he leaves an awful hole, doesn’t he?”

– It’s a Wonderful Life

“The ultimate ideal for a warrior is to lay down his sword.” – Hero

Still, despite varied motivations, we see that our design similarity isn’t limited to a shared impulse to create story; the resemblance bleeds into the narrative structure itself. Throughout all time, all literature, every screenplay or graphic novel, it can be seen: a snapshot of the metanarrative, a piece of its grand frame, a slice of its story, or a distorted, impressionistic broad-stroke of its composition. Because our media centers overflow with variations on the theme, we make absurd statements such as “Hollywood is out of ideas.” Let’s be fair; Hollywood never had any ideas. In a culture where narrative hunger is better rationed, folks join the narrative dance as teller or listener, waltzing in the craft, conflict, and climax of tales that point to our design and our Designer. We, however, stare through insatiable, jaded eyes and lament—like King Solomon—that there is nothing new under the sun.

“All things are full of weariness; a man cannot utter it; the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing. What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun. Is there a thing of which it is said, ‘See, this is new’? It has been already in the ages before us. There is no remembrance of former things, nor will there be any remembrance of later things yet to be among those who come after. What is crooked cannot be made straight, and what is lacking cannot be counted.” – Ecclesiastes 1:8-11,15

Recurring themes needn’t be a source of grief. There may be sadness and boredom if our goal is merely story, but there is joy if reflecting the Designer makes the goal about giving glory. The key is in identifying pieces of the metanarrative, seeing where themes are shared, and where these fit into the frame story of our Designer.

Recurring themes needn’t be a source of grief. There may be sadness and boredom if our goal is merely story, but there is joy if reflecting the Designer makes the goal about giving glory. The key is in identifying pieces of the metanarrative, seeing where themes are shared, and where these fit into the frame story of our Designer.

When a storyteller begins, he establishes the setting with words, or perhaps pictures—an act of creation for the world in which the tale turns. Nipping at the heels of creation enters conflict, like a snake in the grass—an antagonist, the fall, relationship dysfunction, failure. As struggle defines the center of the story, it ultimately culminates in resolution, though not necessarily “happily ever after.” The late Kurt Vonnegut once said grumpily that there was only ONE plot, which he unceremoniously dubbed “man in a hole”—man falls into a hole, man struggles to get out of the hole. In other words, conflict—and the search for resolution—becomes the pivotal structure for all stories.

This isn’t far from the Christian metanarrative, wherein our Storyteller (God—more specifically the “Word of God”) establishes His creation with a line more classic than “Once Upon a Time …” or “A Long Time Ago in a Galaxy Far, Far Away ….” Instead, “In the Beginning …” ushers in creation, followed swiftly by the fall—brokenness, curse, and death—yet carrying the promise of reconciliation and redemption. Whether it’s a Native American oral tradition, C.S. Lewis’ Narnia, or M. Night Shyamalan’s Lady in the Water, we see this cycle surface again and again in other narratives. As The Matrix’s Agent Smith would remind us in expressionless monotone, “It is inevitable.”

Looking at modern storytelling, particularly cinema, we see two overarching categories of narrative structure. One constructs a myopic snapshot that simultaneously rejects and begs for a metanarrative, while the other embraces a measure of metanarrative in some distorted form.

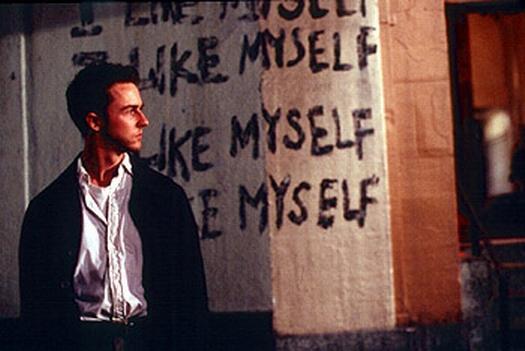

The first, visible in movies such as Citizen Kane, American Beauty, Crash, Blade Runner, and Syriana, depicts how cyclical, lamentable and hopeless life seems. There is no escape, no ascent, and no transcendence. At best, there are moments of temporary respite or distraction. We face a daily grind, accumulating pain, regrets, and eventually death. In many ways, these tales continue the lament of King Solomon in Ecclesiastes.

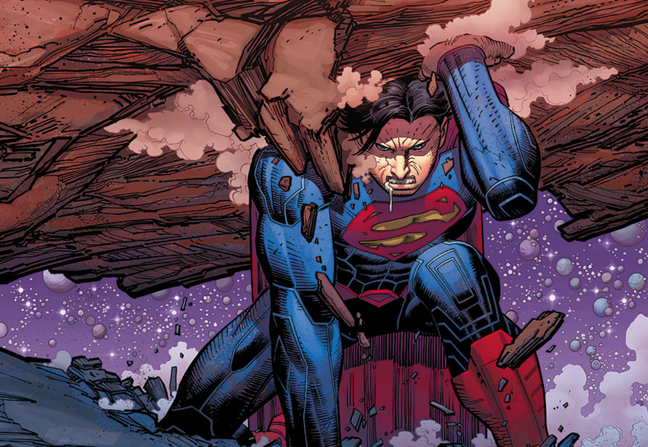

Alternately, heroic tales, such as Superman, The Lord of the Rings trilogy, and The Last of the Mohicans, depict a protagonist, hero, champion, or savior—someone inspiring who rises up, challenges the story’s antagonist(s), and sacrifices himself for others (or at least demonstrates the willingness to do so). Stories with a strong, transcending protagonist laud this champion, who brings hope: a life with at least a glimmer of transcendence from misery, death, and our own depravity.

Why the focus on existential angst? Why concoct a mythical savior? It’s essential we recognize three significant reasons these dichotomous tales emerge over and over in our popular dramatizations, classic myth-making, and man-made religions. First is the recognition that we are created in the image of our Creator. Our God is a Storyteller, and our impulse to weave a narrative tapestry springs from that shared attribute, even if our stories are subsequently spun as a form of defiance against Him. Therein lies the second reason: some regale audiences with tales sans savior, or with a “savior” that looks nothing like (or distracts us from) the true hero of mankind’s metanarrative.

For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who by their unrighteousness suppress the truth. For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them … but they became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened. Claiming to be wise, they became fools, and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and reptiles … they exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator.” – Romans 1:18–25

“You don’t want the truth. You make up your own truth.” – Memento

Like walking and chewing gum at the same time, it takes a talented artisan to hold pen in one hand whilst suppressing truth with the other. Consciously or unconsciously, dismissing the savior, or distorting the savior, is often the personal motivation in telling stories. Still, this doesn’t mean the metanarrative can’t shine through, despite an author’s hidden (even self-deceived) intentions. It often does. THE Storyteller can trump any storyteller, and leverages others to lift the truisms from their texts, as the Apostle Paul did with pagan poetry in Athens.

People who don’t believe in God can be inspired to tell chillingly accurate stories about Satan, as with The Devil’s Advocate. However, our Master Storyteller also motivates allegorical tales and fictional parallels from those who believe the Christian metanarrative. This brings us the third reason for narrative portraits of human depravity and fantastic saviors: Imitation can be the highest form of flattery. Aslan and Neo are both portraits of a savior, but one came from the love of a believer.

At the end of the day, the only difference between allegory and idolatry is the condition of the storyteller’s heart. One crafts a tribute; the other crafts a proxy.

The fruit for reader or viewer is equally subjective; one can watch The Exorcist and develop an unhealthy fascination for the occult; another watches and receives the film as a cautionary tale of our vulnerability to the demonic, drawing closer to the God they trust. One can watch Equilibrium and simply indulge in the kung fu gun carnage, or Christian Bale’s perfect abs, while another sees the amazing transformation of the character and an intriguing parallel with the conversion of the Apostle Paul. One can even watch Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby and see Ricky Bobby’s tragically funny attempts to earn love, instead of running his race because he is loved.

The question is whether or not we are engaging our narrative entertainment with the hope of connecting points to the metanarrative; to do otherwise is at best wasteful, at worst idolatrous.

Joseph Campbell once codified the monomyth—the hero’s journey he found consistent throughout heroic literature. He made no claims these originated from one true myth (as C.S. Lewis would have), but the obvious question emerges: why the similarity? Is there one shared, fabrication of hope in our fiction and religion—with cultural variations—that we coincidentally share across geography and history, when in fact we’re destined to go the way of the dinosaurs and the dodo? Or, is there ultimately a true story of hope that the universe pivots upon? Is there really a false “hero with a thousand faces,” or perhaps a thousand masks, aping a singular truth? Is Jesus the inspiration for these stories throughout human history—fiction and non-fiction—which both precede and follow his incarnation?

Is this something we’ve forgotten or something we’ve suppressed?

“Maybe Rosebud was something he couldn’t get, or something he lost. Anyway, it wouldn’t have explained anything … I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life. No, I guess Rosebud is just a … piece in a jigsaw puzzle … a missing piece.” – Citizen Kane

A word might be insufficient to explain a man’s life, but the Word of our Storyteller creates, defines, and sustains all life. This living Word is the missing piece of a puzzle we rebelliously don’t want to finish. Cutting to the core, every story boils down to that dastardly villain with the waxed mustache, the bound damsel on the train tracks, and the steam whistle death-knell of the mortality train. The only narrative variations are: whether or not there IS a hero riding to the rescue on his white horse and, if there IS, sorting out what he looks like. The Christian points to Jesus as Narrator and Hero, Lord and Savior of the metanarrative, which frames and fleshes out our existence. He is the inspiration for all storytelling that follows in His wake, whether it springs from reverence or denial.

If we humbly approach the art and media of our culture, bearing these factors in mind, we will stop underestimating the power of narrative and engage it in meaningful ways, finding the seed of metanarrative and uncovering how these stories point to, or distract from, the incomparable tale of Truth Incarnate, who has the story on His lips, creation in his hand, conflict under his foot, and resolution in His blood.

James Harleman was born in 1973 and raised in Kent, WA. A quarter-century later he walked into a church and experienced transformation, married his lovely bride Kathryn in October 1999, and completed a bachelor’s degree in Biblical Studies. James has overseen guest services, membership, websites, print publications, programming and staffing for several organizations and teaches classes on Engaging Culture, conducting monthly Film and Theology events.