That Damned Protagonist: Hell Is For Raimi’s Heroes.

Christine Brown has an opportunity.

She lives a callow and unfulfilled life, stuck with a seemingly dead-end job in a bank and a successful boyfriend whose parents don’t want her in his life (lest she embarrass him at the next tennis social). Now, there’s an assistant manager position available for someone with the requisite heart of stone and Christine, unaware of the fates of all other Sam Raimi protagonists before her, abandons decency and refuses to allow a desperate old gypsy woman the third mortgage extension that would save her from eviction.

The old woman, begging and shamed, furiously casts a spell on Christine who now, because of her fatal lack of human kindness, is cursed to spend the next 3 days in torment at the hands of an ancient demon before being dragged to Hell for eternity.

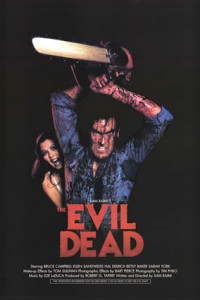

It’s an eventuality many of Sam Raimi’s previous heroes have had to ponder, and one that has required the characters to take drastic and momentous action to avoid. Despite this, the story often ends with these characters as literally and spiritually lost as they ever were. In the 80s, The Evil Dead’s Ash (Bruce Campbell) has to slaughter virtually all his friends to stop the plague of evil spreading beyond an infamous log cabin, and his “reward” is being transported via time-warp to medieval times. Liam Neeson’s deformed, eponymous avenger in 1990’s Darkman (a hugely undervalued forerunner to the Spider-Man franchise), leaves his beloved fiancé, ashamed by his hideously scarred features and his inability to perfect the formula for synthetic skin that would heal him. In Raimi’s Western pastiche The Quick and the Dead (1995), Sharon Stone’s Woman-With-No-Name kills the man who murdered her Father, but like most Spaghetti Western anti-heroes leaves town as monosyllabic and nomadic as when she arrived, spurning the chance to settle down with Russell Crowe’s pacifistic preacher.

Even Kevin Costner’s past-his-best baseball pro in Raimi’s most conventional feature For Love of the Game (1999) has to choose between the love of his life and career. Across the years and genres, these eternal themes are drip-fed into Sam Raimi’s films, clearly repeating beneath his precocious and playful style. The appropriately titled Drag Me to Hell (2009) was the film Raimi acolytes had been waiting for since at least Spider-Man 2 (2004) and maybe even since Evil Dead II (1987). Aesthetically economical and slender, it evokes the supernatural pandemonium and anarchy of his influential debut The Evil Dead (1981), shot with a far more disposable budget as befits the man who has directed three of the biggest blockbusters since the turn of the century.

Even Kevin Costner’s past-his-best baseball pro in Raimi’s most conventional feature For Love of the Game (1999) has to choose between the love of his life and career. Across the years and genres, these eternal themes are drip-fed into Sam Raimi’s films, clearly repeating beneath his precocious and playful style. The appropriately titled Drag Me to Hell (2009) was the film Raimi acolytes had been waiting for since at least Spider-Man 2 (2004) and maybe even since Evil Dead II (1987). Aesthetically economical and slender, it evokes the supernatural pandemonium and anarchy of his influential debut The Evil Dead (1981), shot with a far more disposable budget as befits the man who has directed three of the biggest blockbusters since the turn of the century.

Raimi’s thematic concerns, however, have not changed. Psychological and spiritual issues of guilt, responsibility and a lost eternity are imbedded in the character of Christine. Played with doe-eyed innocence by Alison Lohman, Christine’s situation is made flesh by a visit to a clairvoyant (an occupation central to Raimi’s 2000 chiller The Gift) who reveals that she cannot escape her hell-bound fate unless she is pardoned by her cursor… or if she voluntarily gives the curse away in the form of a token (in Christine’s case, a coat button that was touched by the old woman).From here, Christine begins to reflect the attitudes of many other Raimi protagonists by displaying ruthlessness and contempt for others who do not fit into her plan for absolution.

“Blessed is the one whose sin the LORD does not count against them and in whose spirit is no deceit.” – Psalm 32:2

“Blessed is the one whose sin the LORD does not count against them and in whose spirit is no deceit.” – Psalm 32:2

Like Christine, Hank (Bill Paxton) is driven to defend his immorality in A Simple Plan (1998), Raimi’s most affectingly restrained film. Finding $4.4m in a bag on a crashed plane, Hank’s idea to hide the bounty until he is sure the money isn’t being sought leads him to inadvertently (then deliberately) kill others who might uncover or betray him through their own greed or stupidity. Like Christine, Hank views as insignificant those who he deems morally, socially or intellectually inferior; he frames his drunken, debt-ridden associate Lou and kills his own dim-witted brother Jacob to keep knowledge of the money safe. Similarly, in Drag Me to Hell Christine tries to give the cursed button to the only other rival for the promotion.

By the time he’d made A Simple Plan, Raimi had become more considerate of the consequences of one’s actions than the bombast of his earlier work might suggest. In its source novel (written by Scott Smith, who adapted it for the screen), Hank’s dispatching of his brother happens earlier and with far less reluctance and he murders many more incidental people in a spiralling and macabre finale. Raimi eschews this outcome for a more intimate and tragic conclusion. The novel is about how far you are prepared to go; in Raimi’s hands, the film becomes about how much of your soul you are prepared to lose.

A Simple Plan’s cruel sting is that, unbeknownst to Hank, the serial numbers of many of the $100 bills have been recorded by the authorities and are therefore useless to him. Hank is left in a living Hell, guilt-ridden by his numerous crimes, tormented by the glimpse of a better life and unable to unburden his soul because everyone who was worth confessing to (the local police, his parents, his brother) are all dead or, in the case of his complicit wife Sarah, as culpable as he is.

A Simple Plan’s cruel sting is that, unbeknownst to Hank, the serial numbers of many of the $100 bills have been recorded by the authorities and are therefore useless to him. Hank is left in a living Hell, guilt-ridden by his numerous crimes, tormented by the glimpse of a better life and unable to unburden his soul because everyone who was worth confessing to (the local police, his parents, his brother) are all dead or, in the case of his complicit wife Sarah, as culpable as he is.

It’s also surprising to realize how few decisions Hank actually makes. Keeping the money is Lou’s idea. Framing Lou is Sarah’s idea. Killing Jacob is… Jacob’s idea! The one key decision Hank does make is at one crucial turning point where he has the opportunity to stop the plan spiralling out of control; Jacob has bludgeoned a snooping old man and as Hank goes to dispose of the body, he realises the guy is still alive. He pleads for Hank to call the police. Hank thinks about it. There are two possible outcomes: an assault charge for Jacob and everything just stops, or murder the man and try to keep the money. Hank chooses the latter. It becomes clear that Hank is the weakest man in the story – and the most murderous. He kills more just than the kidnapper who pops up at the end. An easily-led man can be as dangerous as a murderer.

“The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked; Who can know it? I, the Lord, search the heart, I test the mind, even to give every man according to his ways, according to the fruit of his doings. Yet they did not obey or incline their ear, but followed the counsels and the dictates of their evil hearts, and went backward and not forward.” – Jeremiah 17:9-10

Raimi spent nearly ten years exploring these kinds of themes across the three Spider-Man movies (2002, 2004 and 2007) – the idea of otherwise normal people thrown into extraordinary circumstances not of their choosing and left with moral choices that will either cleanse them or condemn them. Peter Parker (Tobey Maguire) blames himself being unable to intervene when his Uncle Ben is shot by a robber. After defenestrating the robber in the first film and establishing that “with great power comes great responsibility”, Parker confesses his role in the killing to his Aunt May in Spider-Man 2. In the third film, Parker believes he has finally killed the actual man who murdered his Uncle and proudly informs Aunt May, fully expecting her to be relieved. “Your Uncle would not want us to live a single day with revenge in our hearts”, is her stern reply. It is only Parker’s decision to forgive the killer that finally absolves his own feelings of guilt and the thirst for vengeance (symbolised by the evolution of the red and blue (stars and stripes) spider-man costume into a black outfit) that has been eroding his soul throughout the whole trilogy.

Raimi spent nearly ten years exploring these kinds of themes across the three Spider-Man movies (2002, 2004 and 2007) – the idea of otherwise normal people thrown into extraordinary circumstances not of their choosing and left with moral choices that will either cleanse them or condemn them. Peter Parker (Tobey Maguire) blames himself being unable to intervene when his Uncle Ben is shot by a robber. After defenestrating the robber in the first film and establishing that “with great power comes great responsibility”, Parker confesses his role in the killing to his Aunt May in Spider-Man 2. In the third film, Parker believes he has finally killed the actual man who murdered his Uncle and proudly informs Aunt May, fully expecting her to be relieved. “Your Uncle would not want us to live a single day with revenge in our hearts”, is her stern reply. It is only Parker’s decision to forgive the killer that finally absolves his own feelings of guilt and the thirst for vengeance (symbolised by the evolution of the red and blue (stars and stripes) spider-man costume into a black outfit) that has been eroding his soul throughout the whole trilogy.

Family audience appeal dictated that Parker would make this decent decision (and reject the black suit), but Raimi has no such qualms in Drag Me to Hell. (Major Spoiler alert! Skip to the questions if you haven’t seen the movie.)

For the first time ever, a Raimi protagonist’s fate is beyond doubt. At its conclusion, Christine believes she has buried the cursed button with the recently deceased gypsy woman, therefore overturning the curse – but we know she has buried the wrong item by mistake. As Christine and her boyfriend realise her dreaded error at a train station, the ground opens up beneath her and monstrous arms pull her down into a fiery pit, skin and hair disintegrating as eyes bulge out of their sockets. In seconds she is gone and the ground reforms, as if Christine had never existed to have stood there. The last thing we see is the boyfriend’s shocked tearful face abruptly followed, like a giant full-stop, by the film’s title and a jolt of Danny Elfman’s score. It’s a conclusion anyone would know is coming, but it is somehow rendered thoroughly haunting through the combination of Lohman’s waif-like presence, a couple of misleading narrative winks, and Raimi’s expert understanding and pre-emption of the genre and its audience.

For the first time ever, a Raimi protagonist’s fate is beyond doubt. At its conclusion, Christine believes she has buried the cursed button with the recently deceased gypsy woman, therefore overturning the curse – but we know she has buried the wrong item by mistake. As Christine and her boyfriend realise her dreaded error at a train station, the ground opens up beneath her and monstrous arms pull her down into a fiery pit, skin and hair disintegrating as eyes bulge out of their sockets. In seconds she is gone and the ground reforms, as if Christine had never existed to have stood there. The last thing we see is the boyfriend’s shocked tearful face abruptly followed, like a giant full-stop, by the film’s title and a jolt of Danny Elfman’s score. It’s a conclusion anyone would know is coming, but it is somehow rendered thoroughly haunting through the combination of Lohman’s waif-like presence, a couple of misleading narrative winks, and Raimi’s expert understanding and pre-emption of the genre and its audience.

Another director may have followed Christine down into Hell and revealed its gruesome, undoubtedly computer-generated terrors or even have let our heroine off completely. But Raimi stays above ground, the finality of the willowy, delicate Christine’s destiny an unfathomable, irreversible and unchangeable reality. It could be the most chilling, decisive depiction of Hell’s power since Rosemary’s Baby, made all the more palpable in that it is glimpsed only briefly and that its terrors are unleashed in reaction to the most common and contemporary of sins such as greed and pride.

If this can happen to the angelic Lohman, I wonder what awaits the Wicked Witch in the forthcoming Oz?

Questions for Discussion:

-

Do you believe you’re essentially good at your core, or inherently corrupted?

-

When and how have you hurt someone (emotionally, physically) so that you might get ahead in life?

-

What have you done in attempts to fix, or atone for, or balance out these misdeeds?

-

Do you believe you can avoid inevitable – even eternal – consequences?

-

Do you spend time floundering in doubt, indecision, fear and self-loathing?

-

What might confession, repentance, and forgiveness look like in your situation?