GRAVITY from down under

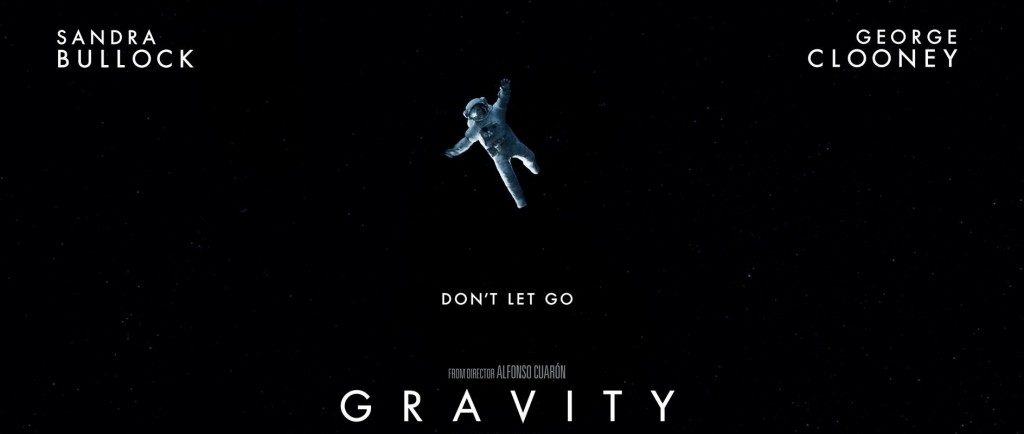

It seems the new film by Alfonso Cuaron orbited into Australia’s view before I could feel the GRAVITY of the hit film starring Sandra Bullock and George Clooney. Guest reviewer Ben McEachen gets the first pass of this film, to be followed by my review next week. – James Harleman

Ryan Stone is in quite the pickle. A debutante astronaut repairing a satellite, elite technician Stone is baptised by a firestorm. Well, a tsunami of space debris, which rains down upon the orbiting transmitter. The satellite is obliterated. Stone is cut loose, and tumbles into the cosmos.

Quite the pickle.

Gravity is a high-concept, high-above-the-earth hybrid of blockbuster elements and art-house interests. Stuff explodes in slo-mo detail. Sequences are tense and death-defying. The 3D experience of Gravity is, arguably, the most immersive since Avatar. Weightless camera-work and fluid editing imbibe viewers into a universe that we seem able to moon-walk in – from our cinema seat.

Also, down-to-earth concerns are brought to the fore, by excellent Mexican director Alfonso Cuaron (who, incredibly, hasn’t made a feature since 2006’s fantastic fable Children Of Men). Closer to contemplative 2001: A Space Odyssey, Moon or Sunshine, than bombastic Armageddon or Independence Day, Gravity is an expansive yet intimate life-or-death mission. At the sharpest point of that spectrum: the terrifying moments before imminent death.

Where better to challenge our precarious existence, than the infinite depths above our heads?

The combination of murderous elements up there – oxygen depleting; zero gravity; no communication with Earth – means Stone (Sandra Bullock) and career astronaut Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) must confront the inevitable…. which we often pretend is somehow avoidable.

What do they do? Stone reacts and Kowalski responds. Stone is frazzled, frightened and realistically pessimistic. Adrift in space, Stone panics. Fair enough. In considerable contrast, Kowalski doesn’t merely react. He responds, rapidly thinking through options and taking action. He is calm, methodical, and optimistic. He’s also quite charming. He’s George Clooney, after all.

But Kowalski’s ability to function under extreme pressure has a progressive, positive impact upon Stone. As he spurs on hopeless Stone, we gravitate to the hope he is buoyed by. We also should applaud his altruistic attitude.

Still, most interesting about Gravity‘s depiction of mortals staring into the Grim Reaper’s eyes, is the shift in Stone.

She goes through a series of emotions, reflections and realisations which believably represent what people experience when death looms.

Previously, her life was highjacked by tragedy. This affects how Stone approaches death. So does the intense knowledge of when her time might be up. ‘Everyone is going to die,’ she pointlessly explains over a spacecraft’s broken radio. ‘But I know when. I’m going to die today.’

While the weakest element of Gravity is its tendency to get preachy or soppy during key speeches, what Stone and Kowalski say – says much about the exercise of existence. When Kowalski challenges Stone’s deficit of joie de vivre, his advice has a Shawshank Redemptive thrust. ‘It’s about how you live, and that you don’t die,’ counsels Kowalski. His overarching ethos is to make the most of everything – no matter what. Good or bad, it’s about how you respond.

Stone does begin to see meaning can be derived, purely, from survival. As if keeping death at bay is a victory for the living. Bolted to this familiar ‘triumph of the human spirit’ fist-pumping is a clear-eyed acceptance that life doesn’t always win. A pivotal scene involves Stone explaining how her ‘story’ (stuck in space; trying to escape) could go either of two ways (life or death). Whichever way it goes, though, it will be ‘one helluva ride’.

Such fatalistic optimism sounds like Gravity presents a universe which includes the universe, us, and nothing else but a pragmatic spring in our step. However, Gravity drops bread-crumbs which lead us to question whether something else is out there. Because, for all the humanism displayed through Kowalski and Stone’s situation, also reflected is how many of us turn to a higher power – when things go bad. Even if we had spent our life, until that point, swearing blind that the idea of God is nonsense and untrue.

Kowalski’s plucky humanism contrasts with Stone mourning how no-one taught her how to pray. Without declaring there is something or someone to pray to, Stone still yearns to be able to pray. Why? Because death looms and Stone is desperate for help in prolonging her life. Are we surprised at such a plea? Not really.

What kind of moment is the moment before death? The clearest display that none of us are, ultimately, in control of our lives.

We like to think we are. Frequently, it can appear as if we are. But even if you can manage your whole life as if you are at the steering wheel, death is the great revealer that everyone will be forced to let go.

Stone’s desire to pray raises enormous questions. What or who is going to answer her? Why should they? Stone hasn’t prayed to them before, and her confession that she doesn’t know how to – suggests she knew could learn. If they did respond to her, what would they say or do? If they are in control and have the ability to save her life, why should they? Maybe it’s her time to let go.

Gravity, then, is a mash-up of self-reliance and the desire for external help. Further complicating this existential collage are references to some kind of after-life, as well as a potent expression of ambiguous gratitude. Indeed, the latter should have viewers leaving the cinema and puzzling deeply over what to make of Gravity’s spiritual implications.

What if Stone is on to something? That there is something else, beyond Kowalski’s coping mechanism of ‘enjoy the ride’? Do we need to be confronted by death, to seriously think about what life is about? Isn’t that leaving it a bit late?

Whether you believe in the significance of his death, you will have heard that Jesus was a man who knew he was going to die. Not just that he would, but how and when. Yes, that is incredible. Before he was crucified, Jesus chose to pray to his heavenly father, God. Yes, Jesus believed in God, who he called ‘Lord of heaven and earth’ (Luke 10:21). Yes, that does mean ‘Lord of everything’. Everything. Including human life.

The gospel accounts of Jesus’ life contain many records of him praying (most famously, ‘The Lord’s Prayer’, in Matthew 6:9-13). Despite knowing when he would die, Jesus chose to pray to God – before death’s door. Unlike Stone, who chose that same moment to desperately begin thinking about the possibility that something else might be in control of her fate.

Jesus consistently acknowledged God as ultimately being in control. So much so that, the night before he knew he was going to be executed, innocent man Jesus prayed to God. Crying out about the agonising sacrifice he was about to make, Jesus still asked for ‘not what I will, but what You will’ (Matthew 14:34). Not what Jesus wants, but what God wants.

Stone considered prayer as a last-minute lifeline. Jesus considered prayer as a last-minute confirmation of his living his life for God, not himself.

Perhaps you don’t understand why God’s will involved Jesus having to die. Or why Jesus placed such importance upon devoting his life to God. Or what your life has to do with recognising the supreme control of the Lord of heaven and earth, as Jesus did.

But you do understand that none of us can control death out of our lives. Death will come. Which should cause us to consider what Gravity hints at, and what Jesus’ life reveals.

If there is someone or something to call out to at the moment of death, why not pray to them during life? Because, as the deep meaning of Jesus’ death and resurrection explains, living is more than what you do on the way to dying.