Star Trek Into Darkness has debuted to positive reviews, and while it may not have boldly gone where no domestic revenue markers have gone before, it’s continuing to perform admirably. Set phasers on thoughtful for this SPOILER-HEAVY yet “fascinating” review by guest Jeremiah Lawson.

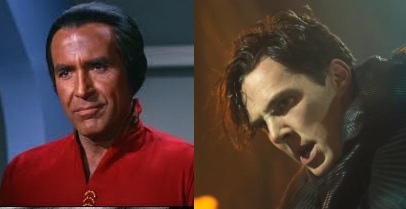

It’s practically impossible to keep from comparing this second film in the rebooted Star Trek universe with the second feature film starring the original cast. However, the real seeds of Star Trek Into Darkness aren’t rooted in the soil of the second Star Trek movie, but rather “Space Seed”, the old episode from the original series and ground from which The Wrath of Khan also sprouted. Upon seeing this new film, connections between all three are easily established, but what also gets revealed is both our changing views as a culture and our unchanging nature.

Contrary to the classic 60s and 80s Star Trek tales that forecast our future course heading, we now know there were never any Eugenics Wars in the 1990s. There was no Khan Noonien Singh, and he didn’t rule anything between 1992 and 1996. The Cold War was over by this time and American popular paranoia shifted from the nuclear Armageddon of Terminator 2 and Watchmen to the cloak and dagger conspiracy theories of The X-Files. History showed us that Roddenberry’s vision of late century darkness before the Federation’s dawn didn’t quite align with reality.

One of the steady critiques of the new J. J. Abrams’ Star Trek film by is that it betrays the progressive secular humanism that was supposed to be the hallmark of this space opera. When Star Trek II: Wrath of Khan hit theaters it was similarly considered a betrayal of the highest ideals and aims meant for the franchise, by no less than series creator Gene Roddenberry himself. (What Roddenberry wanted for his creation was what we got in Star Trek: The Motion Picture… and the film was a critical and box office disaster.)

Nicholas Meyer salvaged Star Trek with 1982’s Wrath of Khan by abandoning what Roddenberry and hard-core Trek fans wanted, to have “the U. S. S. Enterprise as a galactic Peace Corps bringing American- style enlightenment to benighted heathens on faraway worlds.” Meyer instead gave us swashbuckling adventure and character study. The result was a critical and popular success. Betraying the ideology Star Trek was meant to promote and exemplify is what keeps saving the franchise from oblivion and cultural irrelevance.

But we live in a 21st century in which immersive entertainment dominates Western pop culture. In this climate the present is always wanting compared to our emotional investment in the past. We live in a time in which character arcs across three to six seasons are normal. We live in a time in which plot holes are not so readily forgiven by fans. For instance, in 1982 Star Trek fans could watch The Wrath of Khan and hear Khan say “I never forget a face”, even though there was never any indication Chekov was on the Enterprise in season one of the original series. No matter. That was easily explained away, but fifty years and a franchise reboot later there is no such forgiveness from the faithful, is there?

Yet the success of the old Wrath of Khan, compared even to Star Trek Into Darkness, is that Meyer’s 1982 film demands no prior knowledge from you. Everything you need to enjoy the swashbuckling sci-fi meditation on middle-age and failure is in the film itself. Everything you need to know about James Kirk, Mr. Spock, Dr. McCoy and Khan Noonien Singh is contained within the single movie. You don’t even need to watch “Space Seed” (but you should).

Watching “Space Seed” one can see how Khan observed that, in the 23rd century, man has made a few technical advances but that man himself has scarcely evolved at all. This is, in a nutshell, the objection certain Star Trek fans have about the Abrams franchise itself. The special effects and action set pieces are more formidable and expensive, but the human heart beating beneath seems no improvement over what was happening fifty and sixty years ago. A modern-day Marla McGivers might say the men of the old Trek were manlier and more compelling. Maybe they were.

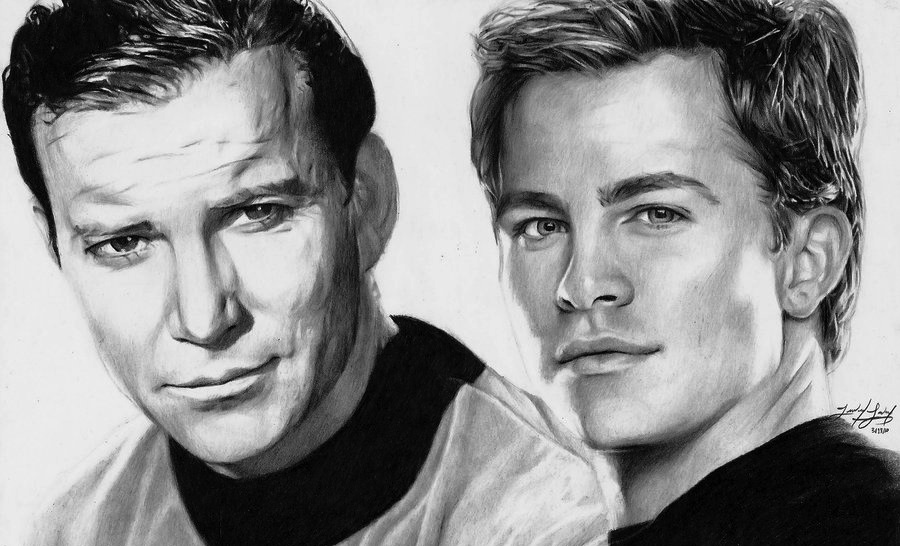

But if we listened to the words of the original James Kirk in that same episode, we’d remember that humanity always has a streak of barbarism in it, appalling but always there. We might also recall his jocular admonition to an incredulous Mr. Spock that it’s possible to admire a man and oppose everything he stands for. It is illogical but utterly true of us. It is an observation the original James Kirk makes that fans watching a new Star Trek may simply wish were not true. But true it is. If Star Trek Into Darkness wants in comparison to Wrath of Khan it’s because Pine’s Kirk is not confronted with middle-age. Pine’s Kirk isn’t forced to simultaneously confront his failures as a captain, lover, and father. Chris Pine’s Captain Kirk has not yet made a string of quick-fix decisions that other people have to pay for. Star Trek Into Darkness gives us an Admiral Pike and an Enterprise crew whose goal is to keep Kirk from ever becoming that kind of man with a “Space Seed” solution.

By the end of that old episode, Kirk defeated Khan’s attempt to seize the Enterprise… but rather than subjecting Khan and his people to the “waste” of a reorientation facility he drops them off on an untamed world for Khan to conquer, a decision Khan proudly approves of and agrees to. Kirk opts to do this and cut off an objection from Dr. McCoy. Spock merely noted that it would be interesting in another century to consider what plant grew from the seed Captain Kirk planted that day. (Of course we all found out what came of Kirk’s confident quick fix… Moby Dick quotes, screaming into a communicator, and tear-inducing bagpipes.)

Of course, the death of Spock in the 1982 film is mirrored by a self-sacrificing Kirk in Darkness. Pine’s Kirk is one who, unlike Shatner’s Kirk, learns early that there are prices that you should not force others to pay for you. This has disappointed some fans who believe the emotional moment was unearned because there have not been decades of continuity. This is mistaken, the poignancy of Spock’s death in Wrath of Khan derived from the story of the film alone. We were shown a Kirk who lectured cadets on how to deal with a Kobayashi Maru test, a test he took three times and cheated to win. This was a Kirk who let other people, from his former lover Carol Marcus, to the son David he never knew about, to Khan Noonien Singh, to his own friend Mr. Spock, pay the price for his clever games at cheating death and consequence. Kirk and Khan were great foils for each other in 1982 because they were both men who had little remorse about using other people toward the end of self-perceived greatness.

Star Trek Into Darkness can neither benefit from nor be shackled by Shatner’s James Tiberius Kirk, and so it gives us a new Kirk who is warned by everyone from Admiral Pike to Scotty that he needs to listen to the crew he’s been given, to let his shipmates and friends second-guess his impulses so that he doesn’t make decisions that will kill everyone he cares about. Star Trek Into Darkness isn’t telling us a story of a Shatner Kirk whose mistakes Spock winds up paying for, it’s telling us the story of men and women trying to keep Pine’s Kirk from becoming Shatner’s Kirk to begin with. Only time will tell if he – or we – will heed the inherently timeless wisdom:

“Without counsel plans fail, but with many advisers they succeed.”

– Proverbs 15:22

(The prolific Jeremiah Lawson has also written a multi-part series on Batman for Mockingbird that’s worth checking out.)