I saw it, and – SHOCK! – it didn’t turn me gay.

I know that a strange contingent of the conservative Christian community seems to think that by the mere watching of a film like Brokeback Mountain – with its “homosexual agenda” – a straight guy might develop a queer eye, but nothing could be further from the truth.

I know that a strange contingent of the conservative Christian community seems to think that by the mere watching of a film like Brokeback Mountain – with its “homosexual agenda” – a straight guy might develop a queer eye, but nothing could be further from the truth.

When I dutifully went to see the film (years ago) it was sold out. I could have chalked up the red flag to divine providence, but I had also tried to see The Ringer and met the same rebuff. Since I didn’t want to believe God was overruling my desire to see the comedic star of Jackass fix the special Olympics, I couldn’t use the same logic to justify skipping Ang Lee‘s controversial film.

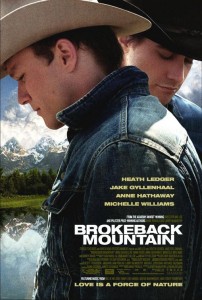

Brokeback Mountain focuses on Ennis Del Mar, played by (the late) Heath Ledger, a tight-lipped redneck ranch hand in the 1960s looking for any work he can get. He and a stranger named Jack Twist (Jake Gyllenhaal) spend an isolated summer on the cold mountain the film is named for, and we discover almost immediately that Jack and his father have apparently never gotten along, and Ennis’ mother and father passed away when he was young (he was raised by a brother, but now feels abandoned). Both men have glaring problems with fatherly and male affection. Moreover, for Ennis summer’s end will bring marriage and responsibilities of husband and future father, which—considering his upbringing—weigh uncomfortably on the young man.

Drinking themselves into a stupor, the two frustrated men eventually engage in a homosexual tryst. Jack seems more comfortable with this, whereas Ennis is initially resistant. The next morning it’s just both of them and the lonely mountain with seemingly no consequences. The relationship continues as they play like boys during the day, shirk their responsibilities, and play lovers at night. The mountain becomes an oasis from the reality below, with responsibilities and expectations ahead. Called down a month early, Ennis is robbed of any chance for conversation or closure.

Drinking themselves into a stupor, the two frustrated men eventually engage in a homosexual tryst. Jack seems more comfortable with this, whereas Ennis is initially resistant. The next morning it’s just both of them and the lonely mountain with seemingly no consequences. The relationship continues as they play like boys during the day, shirk their responsibilities, and play lovers at night. The mountain becomes an oasis from the reality below, with responsibilities and expectations ahead. Called down a month early, Ennis is robbed of any chance for conversation or closure.

Both men marry and have children, but Ennis is a self-centered bigot and a drunk who can’t make ends meet; providing for his family irritates him and he pines for the carefree time he spent with Jack and the intimacy that came more easily. When Twist visits, they abscond to the mountains for “fishing trips”, seeking to recreate their oasis. Over the years, Jack tries to talk Ennis into leaving wife and children, but Ennis wrestles with varied fears and guilt around what he is doing, what that makes him, what others will think or do to them, and more.

Eventually, Ennis’ decisions cost him his marriage and leave his life in ruin, because he ultimately can’t commit to anything: his job, his wife, his kids, or his homosexual lover on the side. The film ends in a rather pitiful tragedy with very little hope for Ennis, living in a trailer with his regret and only a small hope that perhaps he’ll finally invest in the life of his adult daughter.

Eventually, Ennis’ decisions cost him his marriage and leave his life in ruin, because he ultimately can’t commit to anything: his job, his wife, his kids, or his homosexual lover on the side. The film ends in a rather pitiful tragedy with very little hope for Ennis, living in a trailer with his regret and only a small hope that perhaps he’ll finally invest in the life of his adult daughter.

What’s unique about this film is that it does little to assign blame; director Ang Lee has done a masterful job displaying damaged people in a flawed culture who live confused lives. A viewer may assign the blame to culture, Jack, Ennis, adultery, genetics, upbringing, or any number of combined factors. They’ll likely lay the blame according to whatever worldview they walk in with. Some might paint the abusive, drunken Ennis Del Mar as a victim of a culture that would never accept him. Others might point out that this explanation doesn’t justify lies, deceit, adultery, marriage to a woman he won’t love, and horrible parenting. Almost all of Lee’s films (Sense and Sensibility, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, even Hulk) carry an undercurrent regarding life— that it is something laborious that must be endured with great patience, if it can be endured at all. The filmmaker vividly captures King Solomon’s Ecclesiastical lament, that life seems burdensome and wearying and ultimately meaningless. This film depicts a particularly ponderous ponderosa, and Ennis Del Mar is crushed under its weight.

Ultimately, this film portrays the consequences of adultery and an over-idealized tryst. We don’t know what might have happened if Ennis Del Mar had been able to live Jack’s dream of an openly homosexual life. Pinning his demeanor and behavior on that restriction is a big assumption; he might have been an equally ornery, abusive drunk with his male lover once reality set in. The problem with both men—also established early in the film— is not merely that they lacked strong or admirable father figures, but that they don’t know anything about God, and ultimately nothing about love, purpose, direction, or being men, seeking to avoid the rigors and roles of a man and perpetually making life harder for each other, stewing in a poisonous combination of pride, bitterness, lust and self-loathing.

Ultimately, this film portrays the consequences of adultery and an over-idealized tryst. We don’t know what might have happened if Ennis Del Mar had been able to live Jack’s dream of an openly homosexual life. Pinning his demeanor and behavior on that restriction is a big assumption; he might have been an equally ornery, abusive drunk with his male lover once reality set in. The problem with both men—also established early in the film— is not merely that they lacked strong or admirable father figures, but that they don’t know anything about God, and ultimately nothing about love, purpose, direction, or being men, seeking to avoid the rigors and roles of a man and perpetually making life harder for each other, stewing in a poisonous combination of pride, bitterness, lust and self-loathing.

Despite claims that this film in some way promotes some homosexual agenda, Brokeback Mountain does not give us well-balanced gay men oppressed by a conservative culture; it depicts damaged and conflicted men trying to mitigate the pain and void in their lives, with unsatisfactory results.

(originally reviewed for and published at hollywoodjesus.com)

Great review, James. One of my favorite movies of all time.