Bottle Rocket ain’t no trip to Cleveland

review of BOTTLE ROCKET by Zach Malm

starring Owen Wilson and Luke Wilson

directed by Wes Anderson, Rated R

When people ask about my film interests, my joke response is that I generally watch “pretentious” films. I like documentaries, foreign films, slow films. I go out of my way to patronize theatres with only one screen. Also, in that last sentence, I wrote “theatre” instead of “theater”. The fact is, although I do try to avoid pretense, I like arty films, and despite the art crowd’s love of everything Anderson has made after Bottle Rocket, it’s this one, his least “arty”, that moves me the most. It is often chalked up as just another indie comedy, and a promising debut from a director who bloomed later on. I disagree.

When people ask about my film interests, my joke response is that I generally watch “pretentious” films. I like documentaries, foreign films, slow films. I go out of my way to patronize theatres with only one screen. Also, in that last sentence, I wrote “theatre” instead of “theater”. The fact is, although I do try to avoid pretense, I like arty films, and despite the art crowd’s love of everything Anderson has made after Bottle Rocket, it’s this one, his least “arty”, that moves me the most. It is often chalked up as just another indie comedy, and a promising debut from a director who bloomed later on. I disagree.

Bottle Rocket tells a fairly simple story. Three friends in their mid-twenties, Dignan (Owen Wilson), Anthony (Luke Wilson), and Bob (Robert Musgrave), are trying to figure out what they want in life. Anthony is a lonely romantic, Bob a lifelong “little brother”  that wants to prove to his brother that he’s a man, and Dignan is a born leader and eternal optimist with criminal aspirations.

that wants to prove to his brother that he’s a man, and Dignan is a born leader and eternal optimist with criminal aspirations.

Because Dignan is such a leader, and has a tangible goal, he enlists Anthony and Bob to rob a strip mall bookstore, in order to prove his mettle to Mr. Henry (James Caan), a local small-time crime boss who fired Dignan from his front operation, a landscaping company called The Lawn Wranglers. Having pulled off their small heist, the gang goes on the lam, and stays in an out-of-the-way motel for a while. In the span of a few days, Anthony falls in love with a Paraguayan housekeeper named Inez (Lumi Cavazos), Dignan gets in a bar fight, and Bob leaves in the middle of the night to take care of a family emergency.

Once the chaos of the first job is sorted out, Mr. Henry tasks Dignan with planning and carrying out a much bigger job, and when the plan becomes a reality, the friends have to decide if they’re cut out for a life of crime. Since this is a comedy, wacky antics ensue.

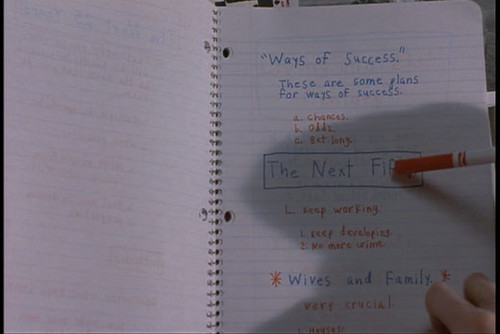

As a Christian in my mid-twenties, I’ve spent much of the last 5 years deciding what I want in life, trying to discern what God has planned for me, prioritizing things in order to get where I think I should be, and working towards my goals. I get lazy, too, but I relate to what these man-boys are going through, and respect Dignan’s drive and ambition. He shows Anthony his 75-year plan in the first 10 minutes of the movie, which includes bullet points for 20 years down the road like “Go legitimate w/Mr. Henry” and “The Robin Hood Principle”, so it’s obvious that to him, crime is a way to get to a place where he can do good things to help others.

As a Christian in my mid-twenties, I’ve spent much of the last 5 years deciding what I want in life, trying to discern what God has planned for me, prioritizing things in order to get where I think I should be, and working towards my goals. I get lazy, too, but I relate to what these man-boys are going through, and respect Dignan’s drive and ambition. He shows Anthony his 75-year plan in the first 10 minutes of the movie, which includes bullet points for 20 years down the road like “Go legitimate w/Mr. Henry” and “The Robin Hood Principle”, so it’s obvious that to him, crime is a way to get to a place where he can do good things to help others.

It’s easy to see that this isn’t the best plan out there, and Anthony knows that after the bookstore job. “Your 75-year plan doesn’t seem to be working,” he despondently tells a jubilant Dignan. “The only thing I’ve learned so far is that crime does not pay.” Dignan, ever the optimist, replies, “Gee man, that’s not the greatest attitude in the world to have. I don’t think we get anywhere by complaining, guys.” We all have goals, but God’s plan is bigger, and part of that plan is to change our heart and make us want to serve him more each day. Dignan is a silly reminder that the ends don’t justify the means, and we can’t cut corners with sin.

It’s easy to see that this isn’t the best plan out there, and Anthony knows that after the bookstore job. “Your 75-year plan doesn’t seem to be working,” he despondently tells a jubilant Dignan. “The only thing I’ve learned so far is that crime does not pay.” Dignan, ever the optimist, replies, “Gee man, that’s not the greatest attitude in the world to have. I don’t think we get anywhere by complaining, guys.” We all have goals, but God’s plan is bigger, and part of that plan is to change our heart and make us want to serve him more each day. Dignan is a silly reminder that the ends don’t justify the means, and we can’t cut corners with sin.

Whatever our goals are, we just have to work, and work hard, and you don’t have to be an adult to understand that. At the beginning of the movie, Anthony, who’s just returned from a mental hospital, tells his young sister Grace that he went there because of exhaustion. “Exhaustion?” she scoffs. “How could you be exhausted? You haven’t worked a day in your life.” Shell-shocked from the exchange, Anthony tells Dignan, who promptly protects his friend from thinking too much about the words of an eight-year old. “What has she ever accomplished with her life that’s so great, man? Nothing. Nothing.”

Ultimately, I don’t love Bottle Rocket for any deep spiritual themes or moral lessons. In fact, I’d guess that the most relevant Bible verses are probably almost all verses in Proverbs about fools. I love Bottle Rocket because it’s a breezy and unpretentious comedy about friendship, growing up, and figuring out what you want out of life. It’s shot fairly straightforwardly, and flows effortlessly, as if all the director had to do was press record. Obviously, this is a very difficult feat to accomplish, especially for a first-time director.  Aesthetically, it’s far more simple than Anderson’s other films, which put more and more emphasis on visual style with each successive film, culminating in his heartless diorama The Life Aquatic (his follow-up The Darjeeling Limited reined that in well, and ended up being a very fine film, with a trio of brothers that reminded me a lot of the Bottle Rocket gang).

Aesthetically, it’s far more simple than Anderson’s other films, which put more and more emphasis on visual style with each successive film, culminating in his heartless diorama The Life Aquatic (his follow-up The Darjeeling Limited reined that in well, and ended up being a very fine film, with a trio of brothers that reminded me a lot of the Bottle Rocket gang).

The performances by all the actors, including Luke and Owen Wilson, all feel natural. Nobody was a star, and with the modest budget and story it’s doubtful that anyone figured this was a ticket to stardom. Owen Wilson, who wrote the script with director and roommate Wes Anderson, had never even planned to act in the movie, since he considered himself to be a writer. The fact that he’s an A-list actor now is basically an accident. Bottle Rocket, however, is no accident. It’s a unique, thoughtful, and funny debut from a brilliant director that deserves just as much acclaim as Anderson’s later films, if not more. I for one would love to see Anderson make another film without his usual bag of tricks. For now, I’m content with picking up the long-awaited Criterion special edition and watching it another hundred times.