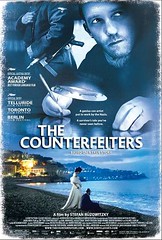

The Counterfeitors

A review of THE COUNTERFEITORS by Aaron Webb

A review of THE COUNTERFEITORS by Aaron Webb

directed by Stefan Ruzowitzky, Rated R

The Counterfeiters is an Austrian film which tells the story of Salomon Sorowitsch, a master counterfeiter who is forced to work for the Nazi’s in their attempt to destabilize the currencies of their wartime enemies. Directed by Stefan Ruzowitzky (All the Queen’s Men) the film takes the viewer through wartime intrigue to explore themes of morality and survival.

Recently, Germany and Austria have turned out some striking period films, the most notable being The Downfall, an intense illustration of the final 12 days of Hitler’s Life; and The Lives of Others, a story set against the background of Secret Police monitoring in East Berlin during the 1980’s. The Lives of Others won the 2007 Oscar for best foreign film, and The Counterfeiters followed in its footsteps for 2008 – deservedly so.

The production is carried out well with realistic and historically accurate sets and costumes. The story is bookended with events occurring in Monte Carlo after the war is over and the majority of the movie is told as one long flashback. The cinematography during the Monte Carlo scenes is stable while the camera during the flashback (and most of the movie) follows a point of view style that makes the viewer feel like they are seeing the memory first hand. Director Ruzowitzky commented that they intentionally did not film a single scene without Sorowitsch in it. Many of the scenes open with the camera looking over the shoulder of Sorowitsch causing the audience to start each scene from his perspective. When the film opens in Monte Carlo, the colors are vibrant. Once the flashback starts and Sorowitsch is arrested, the colors become very muted and washed out. The transition at the beginning of the film between the vibrancy of Monte Carlo and the flatness of the flashback after his arrest is done so seamlessly that I didn’t realize it until the action returns to colorful Monte Carlo at the end and I was left wondering if the rest of the film had been in black and white. A running theme through the scenes in the concentration camps is that they live in a world without color. This is true literally on film, and in the story as all the art that the prisoners do is without pigment which they do not have access to except when counterfeiting.

The acting is superb with Karl Markovics as the enigmatic Salomon Sorowitsch, August Diehl as idealistic Adolf Burger and Devid Striesow as Strumbannführer Friedrich Herzog. The direction by Ruzowitzky really builds the chemistry between Markovics and Diehl. These actors do a fantastic job of balancing the line of respect and enmity between Sorowitsch and Berger.

The Counterfeiters is a fictionalization based on the true story of Operation Bernhard, the Nazi attempt during the Second World War to print enough counterfeit British Pound notes to destabilize the economy of the United Kingdom. It is things like Operation Bernhard that make the Nazi’s great villains for the likes of Indiana Jones and Rick Blaine to fight. This is because they really would try anything if they thought it would give them an edge: Find the Ark of the Covenant (Raiders of the Lost Ark), Open a gate to hell (Hellboy) and print £134,610,810 in perfect British currency (true story).

The absurdity of the idea is tempered by the real life success. The notes from Operation Bernhard were so good that they were called  “the most dangerous ever seen” and to this day remain some of the most perfect counterfeits ever produced. Operation Bernhard was enough to create paranoia in the Bank of England which pulled all notes larger than £5 from circulation for 20 years. But rather than trying to flood the economy of the United Kingdom the Germans decided it would be more effective to use the currency to fund intelligence operations and pay for strategic imports. They started trying to counterfeit the American dollar, but were unable to get it out before the end of the war. The film is loosely based on real-life counterfeiters Salomon Smolianoff and Adolf Burger, a printer whose memoirs were used to write the screenplay.

“the most dangerous ever seen” and to this day remain some of the most perfect counterfeits ever produced. Operation Bernhard was enough to create paranoia in the Bank of England which pulled all notes larger than £5 from circulation for 20 years. But rather than trying to flood the economy of the United Kingdom the Germans decided it would be more effective to use the currency to fund intelligence operations and pay for strategic imports. They started trying to counterfeit the American dollar, but were unable to get it out before the end of the war. The film is loosely based on real-life counterfeiters Salomon Smolianoff and Adolf Burger, a printer whose memoirs were used to write the screenplay.

The plot centers around one man, Salomon ‘Sally’ Sorowitsch, who is arrested in 1936 Berlin for counterfeiting. He is sent to a labor camp and later, as the Nazi regime takes control, a concentration camp. Several years pass and through his skills in art he receives protection and some comforts from the guards who assign him assorted projects. This gets him noticed and he is transferred to Operation Bernhard, run by Herzog, the man who first arrested him in 1936. It is in Operation Bernhard where we see the real drama open up. Sorowitsch faces several situations where his actions and reactions seem contradictory. The counterfeiters live in relative luxury compared to the rest of the concentration camp inmates, even thought the Nazis are constantly threatening to kill them if they do not produce successful counterfeit notes in time. Many of the workers fervently work to meet the deadlines in order to preserve their own lives. An idealist, Berger tries to sabotage the operation because he would rather die than help fund the Nazi war effort. Sorowitsch diligently works on the Nazi counterfeiting project, but his reasons are much more ambiguous. In the opening sequence of the film, Sorowitsch appears to live the high life with lots of money and women, but the film reveals him as an empty and wounded man that emigrated from Russia to Germany after losing his wife and children.  His outlook on life, at least his own, is more pragmatist than optimist, and it does not feel like he’s only trying to stay alive. Some accuse Sorowitsch of professional pride that drives his desire to accomplish his lifetime goal of counterfeiting the American dollar regardless of the moral cost. Sorowitsch may not care about his own life, he may be filled with pride, he may fight doggedly with the more outwardly selfless Berger, but at the same time the film does not show Sorowitsch to be a man without hope or let us cast him off as a monster. Although Sorowitsch and Berger are constantly fighting amongst each other, Sorowitsch also repeatedly defends Berger against the others and refused to expose his sabotage efforts. Sorowitsch’s compassion for a young boy that is a member of the counterfeiting team further obfuscates where exactly Sorowitsch’s heart lies and what is truly motivating him.

His outlook on life, at least his own, is more pragmatist than optimist, and it does not feel like he’s only trying to stay alive. Some accuse Sorowitsch of professional pride that drives his desire to accomplish his lifetime goal of counterfeiting the American dollar regardless of the moral cost. Sorowitsch may not care about his own life, he may be filled with pride, he may fight doggedly with the more outwardly selfless Berger, but at the same time the film does not show Sorowitsch to be a man without hope or let us cast him off as a monster. Although Sorowitsch and Berger are constantly fighting amongst each other, Sorowitsch also repeatedly defends Berger against the others and refused to expose his sabotage efforts. Sorowitsch’s compassion for a young boy that is a member of the counterfeiting team further obfuscates where exactly Sorowitsch’s heart lies and what is truly motivating him.

Ruzowitzky did not want the morality to be cut and dry. In an interview, Ruzowitzky says that typical concentration camp inmates did not have the luxury of making moral decisions. In addition to beds with sheets and a ping pong table, the counterfeiters are given the privilege of having moral decision making. Everybody wants to do what is right, but the concentration camp system was built so that it was very difficult to do the right thing in such a place. What we (and Ruzowitzky) don’t realize is that the situation of the counterfeiters portrayed by Ruzowitzky in the concentration camp is a microcosm of the real world. We are fooling ourselves if we think that we are not in the same situation as Sorowitsch every second of every day. We are all caught in a struggle between idealism and pragmatism. In the film Sorowitsch states, “Nobody’s prepared to die for a principle,” to which Berger replies, “That’s why the Nazi system works!” This echoes Proverbs 28:12: When the righteous triumph there is great glory, but when the wicked rise, people hide themselves. The proverb shows how this internal struggle plays out. When it seems like evil is winning people become ever more pragmatic, looking out for themselves and their own. Pragmatism becomes so overwhelming that the ideal of righteousness is lost and what is right becomes relative. Everyone did what was right in their own eyes (Judges 21:25). Ruzowitzky shows us this in the way that he sets up the characters. With each character he tries to create a situation where the viewer says “That is exactly what I would have done,” accentuating the false sense of relativism between right and wrong. Our longing for an ideal comes from the deeper desire for there to be a truth. Thankfully, we can rest in the words of God; “I the Lord speak the truth; I declare what is right” (Isaiah 45:19).

Did Soloman Smolianoff have any children? Was he married? Are there any relatives of Smolianoff?