The Devil You Know

A review of “The Exorcist”

A review of “The Exorcist”

by James Harleman

Director – William Friedkin

Writer – William Peter Blatty

Ellen Burstyn – Chris MacNeil

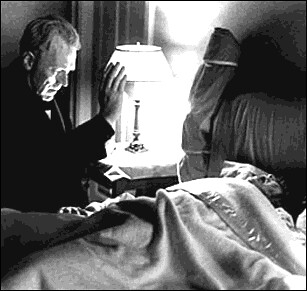

Max von Sydow – Father Merrin

Jason Miller – Father Damien Karras

Linda Blair – Regan MacNeil

From a filmmaking perspective, the power of “The Exorcist”, directed by William Friedkin and based on the book by William Peter Blatty, lies not in its gory visuals, or the flashes of demonic faces and images sprinkled generously throughout, but truly, ultimately, in the audio track. From the opening scene in Northern Iraq, with the sonic dissonance of a hundred pickaxes and the sound of hammers beating out metal on an anvil as the brilliant Max von Sydow struggles to choke down his heart medication, the film claws at your nerves in every scene. Even a harmless downstairs moment between Father Karras and the possessed girl”s mother is made edgy by a rasping steam iron that hisses in and out like the demonic Linda Blair”s hyperventilation. As the soundtrack alternates between Oldfield”s seemingly mellow Tubular Bells and quick violin strings that strike without warning, the viewer is never allowed to relax, even when the scene is clearly removed from the source of danger. (It didn”t hurt, either, that the Cinerama had the THX system maximized to the extent that the opening advertisement rattled my rib cage.)

Of course, the visuals are so raw, and subject matter so intense, that they combine with the audio experience to create-even by today”s standards-a truly repulsive film. Don”t misconstrue my meaning; I do not employ the term “repulsive” as a negative connotation toward the film per se. Indeed, it truly seems the director”s (and Blatty”s) intention to mortify the viewer with the sheer demonic depravity to which this poor girl and her mother are subjected. They succeed. or perhaps they overachieve. Let me explain.

For those who missed the last twenty years, let”s have a quick review: “The Exorcist” opened on December 26, 1973, and moviegoers were soon passing out in the theatre and fleeing the movie houses, much like they did later with “Alien” in 1979. The Skinny? A demonic presence takes possession of a popular actress’ young daughter. When the non-religious, divorced Chris MacNeil finally faces what is truly causing her daughter”s “condition”, a local priest (Damien Karras) trained in psychology who has “lost his faith” is drawn into the horrible events. Together with the experienced Father Merrin, they attempt to free the girl from her tormentor, with questionable results. The movie wins an Academy Award, but is largely shunned by the Christian community. Now, fast-forward 27 years. in the grand Lucas-ian tradition of “Special Editions”, someone decided it was time to add a few deleted scenes to The Exorcist and re-release it for the desensitized, over-stimulated year 2000 viewing audience.

End result? Well, I gaze back upon the glut of horror films of the last three decades, and most of them still pale by comparison.

Indeed-while a non-Christian views this film as they would watching a horror film about extra-terrestrials (i.e. “this stuff doesn”t happen in real life”)-the two non-believers I attended the film with found the film terrifying, even by today”s grisly standards. The flash-frames of demonic faces lurking in unexpected scenes, the chilling image of a gargoyle half a world away appearing on the wall, and the added scene of the girl descending the stairs and vomiting blood, made my epidermis crawl out of the theatre. It hung out in the lobby while my exposed muscles and nerve endings twitched for the remainder of the film. Moreover, in a culture that elevates and reveres the innocence of its children, watching the possessed, pre-pubescent Regan indulge in sexual sado-masochism and listening to her spit the vilest obscenities at her visitors breaks nearly every American cultural standard. This isn”t about campers getting chopped up by chainsaws, murdered in their dreams, or killed by urban legends; this is about the explicit violation of a little girl.

Moreover, I would contend that the film also strikes a subliminal chord (that non-Christians will deny), in that it presents a fictional account of a force that is real rather than fairy tale, chronicling a modern-day version of possession that has occurred in the past, and may still occur today. In a western context that largely denies such phenomena, I could argue that-from a strategic perspective-it appears smarter for demonic forces to NOT present themselves. However, demon possession is a real event according to scripture, and stories of its presence in the eastern world or less “developed” nations are still reported. I think, either way, Friedkin”s film version of Blatty”s book has power because it deals with something-deep down-we all know to be real.

Moreover, I would contend that the film also strikes a subliminal chord (that non-Christians will deny), in that it presents a fictional account of a force that is real rather than fairy tale, chronicling a modern-day version of possession that has occurred in the past, and may still occur today. In a western context that largely denies such phenomena, I could argue that-from a strategic perspective-it appears smarter for demonic forces to NOT present themselves. However, demon possession is a real event according to scripture, and stories of its presence in the eastern world or less “developed” nations are still reported. I think, either way, Friedkin”s film version of Blatty”s book has power because it deals with something-deep down-we all know to be real.

Yet the film”s most powerful message is not demonstrated by Linda Blair”s possession. The most vivid illustration in the film is when this poor girl”s peculiar “condition” is first identified. It exposes the flaw not only in the way the secular world views reality, but the “cultural lens” through which even Christians often view, and deal with, problems. When young Regan first manifests her behavior, she is subjected to a nearly endless battery of physical tests. Only when every empirical test has been exhausted (multiple times) do they turn to the “less credible” alternative. psychology. Then, when the country”s best psychologists have tapped their theories and resources to no avail, one finally suggests Regan”s mother seek “religious help.” Even then, the psychologist purports that exorcism only works because “a person believes so strongly that they are possessed”, (and hence believes strongly in exorcism), that the ritual works “because their own mind convinces them they are cured”. Wow. all hail the mighty, unfathomable power of the human mind. This mindset proposes about the human mind what Homer Simpson proposes about beer: “the source of-and solution to-all life”s problems.”

And yet, as Christians, even I fall prey to this three-tiered form of dealing with issues in my life. Even something as trivial as lost keys follows this pattern: I exhaust every physical way of searching, then sit and attempt to mentally visualize where I left them. Only after these methods do I remember-as the last-ditch alternative-to pray about it. Finding the keys tends to occur later, by accident or a sudden illumination. I”m not alone in this; many of us forget to go to God first with issues both large and small. Instead of turning to prayer and scripture for help in an everyday context as our initial response to a problem, God becomes our embarrassing little backup plan for those “rare” times we can”t solve a problem “ourselves”.

The Exorcist presents this misguided methodology quite plainly, although the initial diagnosis of Regan”s doctor-to put her on Riddlin-elicited laugher from the audience, so most probably missed the point. In fact, that”s one way The Exorcist dates itself. society has flopped the first and second forms of testing; they tend to send their kids to the shrink before seeking medicinal treatment for behavioral issues. However, even if medicine and psychology have swapped or integrated, God still holds last place in the hearts of “rational” society.

Also interesting is the question that the film never answers directly; it is queried several times why this is happening to the poor girl. The mother wails with wonder about how this can be happening, while at the same time professing that she doesn’t believe in God. Not only does she get angry when she finds a cross in her house, but she takes the name of Christ in vain so often-I didn”t keep count, but possibly more than her demon-infiltrated daughter. When her daughter pulls out an ouija board, Chris is merely curious and lets her daughter demonstrate. There is a lesson to be learned here, and the film lets it hang in the air. It”s the old “why do bad things happen to good people?” question, and I think the film opens up conversation to that end. Scripture is clear that a demon cannot enter where the Holy Spirit dwells. Anyone else leaves themselves open to invasion, similar to the humans in “The Matrix” who were able to be overwritten by the “Agents”.

Priests were also dealt with appropriately in the film. Damien Karras suggests at the film”s beginning that he has lost his faith (no reason to get into an election debate here-whether he “lost it” or ever had it is not the issue here): he also keeps leaning on psychology even when the truth of Regan”s possession has been made apparent. Though he means well, his faith is not in Christ, which explains what happens to him in the film”s climactic scene. Father Merrin, in contrast, is dedicated and sincere; he also commands the demon to come out by the power of Christ, unlike a plethora of films I”ve seen where the man of God says “by the power of Christ I cast you out! I command you. Waaaay too many I’s tossed around. Merrin reminds the demon not to “reject the command because you know I am a lowly sinner. It is the power of Christ that commands you. It is by the Father, and the Spirit.” etc. He does not assume being a Christian gives him personal power; he is humble, relying on God”s power to effect change.

In the end, however, I felt uncertain whether I should recommend “The Exorcist” or not. From audience reaction-and the non-Christians present that I knew-I don”t think any non-believers left wondering if God or the Bible might be true. In our pluralistic culture, admitting the existence of demons has no inherent connection to believing in Jesus Christ or the God of the Bible. On the other side, it is so visually disturbing that most Christians will find it excessive and gratuitous. The messages in the film I spoke about above are conveyed in more depth in other films. Yet I can”t know everyone”s heart; it may have slapped more than one complacent Christian in the face, or prompted a lapsed Catholic to renew a relationship with Christ.

As a film, “The Exorcist” was a work of cinematic art. The imagery, acting, and nuances are superb. As a cultural tool for the Christian to employ? I remain uncertain. I”m glad I reviewed the film-as a westernized Christian I am too often the skeptic in regard to modern miracles or, in this case, possession and exorcism. It was a powerful reminder that what we deem “reality” is a pale shadow of what Scripture tells us lies behind the curtain.

I do not, however, feel the need to see the film again anytime soon.

I have never managed to watch this movie to the end. But I tend to be very sensitive to children being abused in any manner in book, film or otherwise.

> ” God becomes our embarrassing little backup plan for those “rare”

> times we can”t solve a problem “ourselves”. ”

I also fall into this trap and catch myself sometimes. And sometimes not. Usually I get convicted for not going to JC first. Still a lot of cultural conditioning to be undone (not to mention my innate sin corrupted nature).

It’s a wonder God puts up with me. I know I wouldn’t.

/mm

This is a great review! I love reviews that are backed by film studies, especially reviews that focus on diegetic sound. I realize that it’s natural to focus on that, given the nominations, but it’s rarer for reviewers to train their attention on sound.