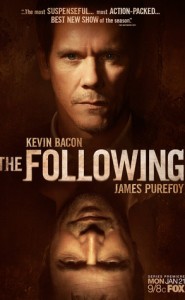

Are you following THE FOLLOWING?

“My masterpiece will be finished soon. I can’t wait for you to read it.” – Joe Carroll

Over 20 million people turned out to watch The Following, the gritty drama where we discover a serial killer has used his potent powers of persuasion to produce a pervasive cult-like group that is carrying out his grand vision. That means, (if we’re inspired by the pseudo-scientific theory of “six degrees of Kevin Bacon“) that even if you’re not watching the new FOX series, somebody you know is addicted to this show.

The premise is revealed quickly, in which we discover imprisoned Joe Carrol (James Purefoy) has created a “following”, religious and devoted in their zeal and adhereance to his allegedly Edgar Allen Poe-inspired vision of life, death, and the world. Ex-FBI agent Ryan Hardy (Kevin Bacon) is brought back to help investigate and stop Carroll’s machinations, but assumptions of how deep the organization goes are woefully underestimated.

“There’s a vacancy in our humanity.” – Debra Parker

Some have complained about the violent, gory intensity of the show. Robert Bianco of USA Today called it “one of the most violent, and certainly the most frightening, series ever made by a commercial broadcast network.” However, considering the CSI and other abbreviation-procedurals out there and even funnier shows like USA’s Psych, I liked what the New York Times’ writer Alessandra Stanley said: “The Following offers a more salutary depiction of violence than do series that use humor to mitigate horror — and thereby trivialize it.” Good arguments could be made on both sides, but cutting homicide with humor could be equally accused of glorifying it. Showing it in all its unvarnished depravity might actually make it less compelling.

There is, however, a chink in the armor here that makes for intriguing conversation. While we’re clearly supposed to view Bacon’s character Ryan Hardy as the protagonist, his character is far less compelling to the viewer. Carrol’s charisma may not make you want to sign up for his following, but Purefoy’s presence and the writing of his character are certainly more interesting than Ryan. Kevin Bacon handles his character well, unsure of himself and seemingly lacking any foundation of his own. But what does he have to offer as an alternative to Carrol’s calling? He’s a drunk, a loner, with a tell-tale bad heart, at a place of emptiness and failure in his life. Fortunately this is a series, so the idea is that we’ll ultimately see something worth following that’s a better alternative than the twisted vision of his nemesis. However, we don’t live in the black and white world of yesteryear, do we? Culture isn’t satisfied by the automatic assumption that the “right” way is God and country. Hardy can’t remain a cardboard cutout of assumed virtue for long: we have to understand why he’s right if the story is going to have longevity.

“Good and bad no longer existed.” – The Gothic Sea

Some have also criticized the show’s use of Poe as light, surface-skimming, and even missing the point. As a man who owns Poe’s collected works (and used to be obsessed with Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment) I resonate. Sometimes my musings about how, apart from Christ, I might have become a serial killer… are only half-joking. There’s something compelling about a man who casts off conventional morality, calls into question the social morays, and invites us to free ourselves from the shackles of subjective group-think. It’s pointed out that Carroll is luring followers with literature and ideas that emerge from romanticism, a reaction against the scientific rationalization of nature. Creation is important, whereas to be derivative is the worst sin.

“It’s so wonderful to see so many of you here. Together we can create a beautiful story.” – Joe Carroll

“Story-formed lives” is a popular concept in culture, in Christendom, and certainly here at Cinemagogue… and it’s a heartbeat writers of The Following have obviously put their finger on. Joe Carroll sees life as story, and invites his followers to be participants and even help by writing chapters of it. This language isn’t uncommon, but it’s foundation isn’t undergirded by our present, predominant, and purely naturalistic understanding of the universe wherein we come from nothing and go to nothing. Joe exploits only half of truths that I believe… that life and death have meaning, that we participate in it, that there are truly antagonists and protagonists. The problem is he takes half of these truths and makes a turn to crazy town. He bends truth to his vision, a story he is controlling, and appeals to something Hardy’s boss Debra points out poignantly.

“We all want to belong. It’s a primal need.” – Debra Parker

Carroll even goes further than your typical cult leader, in that he’s not simply putting willing followers into his story: he’s repeatedly voiced that he’s giving Hardy purpose, he’s providing Hardy direction: he’s providing Kevin Bacon’s character with a story wherein he gets to be the tragic hero, the man who has to come from behind and overcome his own limitations to thwart his enemy. Take a step back for a moment… is he right in a way we haven’t considered yet? Would YOU watch the story of Ryan Hardy without Carroll, without the following? Would you be tuning in week after week for a tale of “has-been, mopey time” around the washed-up Hardy house? Doubtful. We’re engaged by the tale for the same reasons that the seemingly demented Carroll suggests he’s “writing it” for Ryan. In fact, I started watching it because so many people were talking about it, because it had… quite a following.

Carroll even goes further than your typical cult leader, in that he’s not simply putting willing followers into his story: he’s repeatedly voiced that he’s giving Hardy purpose, he’s providing Hardy direction: he’s providing Kevin Bacon’s character with a story wherein he gets to be the tragic hero, the man who has to come from behind and overcome his own limitations to thwart his enemy. Take a step back for a moment… is he right in a way we haven’t considered yet? Would YOU watch the story of Ryan Hardy without Carroll, without the following? Would you be tuning in week after week for a tale of “has-been, mopey time” around the washed-up Hardy house? Doubtful. We’re engaged by the tale for the same reasons that the seemingly demented Carroll suggests he’s “writing it” for Ryan. In fact, I started watching it because so many people were talking about it, because it had… quite a following.

It’s curious to me that the cultural question about the show’s violence might be a pale imitation of the same question about the actions of Carroll’s ardent supporters, and even more curious that there’s a vacancy in any meaningful rebuttal on the side of the show’s protagonists. Do we have any grounds to say what they’re doing is wrong in any objective sense, beyond the law of the land or a poor parent’s reply of “well… because!” I’ve been blessed with a gift: the faith and belief in a storyteller who declared life and death have purpose, and that everyone – even those who oppose Him – play a part in His grand design. Sound familiar?

“In love he predestined us for adoption as sons through Jesus Christ, making known to us the mystery of his will, according to his purpose, which he set forth in Christ as a plan for the fullness of time, to unite all things in him, things in heaven and things on earth.” – Ephesians 1

Joe Carroll is compelling because he presents a wisdom that is counter to the world, but the problem is that he has effectively declared himself God. Apart from this, I wonder who might have a viable answer to counter Joe Carroll. As we see in the series, Ryan often finds himself obstinate but at a loss for words. It’s like seeing a religious zealot thwarting the agnostic while both of them stand far from the truth. Ryan knows in his soul that Joe’s way is wrong, but he has about as much ability to counter the argument as he has at healing his damaged heart. If only he knew the real truth that could do both…

“For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them.” – Ephesians 2

At one point Debra points out to Emma (one of the followers) that she didn’t “free herself” by killing her mother. She only traded one dictating parent for another, now enslaved to Joe Carroll. Emma simply traded one form of slavery for another. Debra successfully stabs at the problem but can’t illuminate any true solution; she has no greater truth to invite the girl into. The show can say what we should run from, but not what we should run to. They can’t even assign blame! Critics have noted the show’s characters try to lay some fault at the internet, or maybe Poe, but there’s nothing it can really commit to without offending someone. The brokenness and hopelessness in the eyes of the those struggling against Carroll’s plans only add to the conundrum, and I hope it’s something the series seeks to tackle in seasons to come. Until then, it might make for great philosophical and spiritual discussion around the water cooler.

At one point Debra points out to Emma (one of the followers) that she didn’t “free herself” by killing her mother. She only traded one dictating parent for another, now enslaved to Joe Carroll. Emma simply traded one form of slavery for another. Debra successfully stabs at the problem but can’t illuminate any true solution; she has no greater truth to invite the girl into. The show can say what we should run from, but not what we should run to. They can’t even assign blame! Critics have noted the show’s characters try to lay some fault at the internet, or maybe Poe, but there’s nothing it can really commit to without offending someone. The brokenness and hopelessness in the eyes of the those struggling against Carroll’s plans only add to the conundrum, and I hope it’s something the series seeks to tackle in seasons to come. Until then, it might make for great philosophical and spiritual discussion around the water cooler.

“…when you did not know God, you were enslaved to those that by nature are not gods. But now that you have come to know God, or rather to be known by God, how can you turn back again to the weak and worthless elementary principles of the world, whose slaves you want to be once more?” – Galatians 4

Questions to consider about The Following:

- Do we believe life and death have meaning, purpose, even romantic design?

- Why DO we feel a need to belong?

- Do we believe we are part of a story being told in which we are a part?

- Does the “side of right” in the show (Hardy, others) have anything to offer more compelling than Carroll’s vision?

- If there is a vacancy in our “humanity” what caused it, or what causes it, and what will TRULY fill it?