Live. Die. Keep going. Why?

Live. Die. Keep going. Why?

I’m biased. I’ve been into The Walking Dead for over a decade, having picked up the first issue of the comic book in 2003 and following the travels of Rick Grimes, his family, and various survivors in a zombie apocalypse. The first issue came out roughly the same time as the pseudo-zombie hit 28 Days Later, and years later the third season premiere of The Walking Dead would become the most-watched basic cable drama telecast in history. The mid-season finale pulled in 15.2 million viewers for and became the first cable series to beat every other show of the fall broadcast season in the adult 18-49 demo.

So like every arrogant fanboy, I think my opinion matters more because I was there at the REAL beginning.

I think the television show has swung wildly in quality, struggled with consistency in writing and acting, and generally hasn’t lived up to the excellently written comic. I have on my side the fact that – behind the screen – production has seen massive turnovers – writers, a showrunner (twice) and more – so there is certainly some truth here. That being said, The Walking Dead on AMC retains enough of the source material’s heart to captivate a much larger audience, and changed the cultural mindset that once considered the genre as something lesser. The zombie apocalypse narrative has earned a place as respectable drama, where some of us long thought (or hoped) it belonged.

I think the television show has swung wildly in quality, struggled with consistency in writing and acting, and generally hasn’t lived up to the excellently written comic. I have on my side the fact that – behind the screen – production has seen massive turnovers – writers, a showrunner (twice) and more – so there is certainly some truth here. That being said, The Walking Dead on AMC retains enough of the source material’s heart to captivate a much larger audience, and changed the cultural mindset that once considered the genre as something lesser. The zombie apocalypse narrative has earned a place as respectable drama, where some of us long thought (or hoped) it belonged.

The intriguing storytelling ability of The Walking Dead is that most zombie stories only give us the first few days, or months, of the apocalypse: we typically follow a band of people and their short-lived story or conflict in 90 minutes, sometimes 120. A series – comic or television – allows the storyteller to explore a vast array of social mores, the unravelling of our cultural mindset and how the fabric is knit together in light of a radically changed landscape. The comic has shown Rick’s small pocket of humanity deal with questions concerning male and female roles, capital punishment, children handling firearms, religion, even polygamy.

-

What if there are more women than men?

-

What do we do with someone who murders another human?

-

How do kids grow up seeing parents shooting “walkers” and not have this alter their view of human life and dignity?

-

Is there any value or point in having children anyway?

-

With no government, no law outside your group, how do you decide rules of order? Right and wrong?

-

How do you determine who is part of your “group”, accepting or turning away others?

-

Do you want to stay small and nimble, or is there safety in numbers?

-

Is the ultimate plan simply to isolate and survive, or establish and rebuild?

The questions seem endless, which can lead to plenty of great discussion material after an issue or episode ends.

Writer/creator Robert Kirkman (who works on both the comic and television show) professes to be an atheist, and while the book has shown supporting characters discuss God and religion, it isn’t central to protagonist Rick Grimes, or the main thrust of characters and their decision-making. This is understandable, but intrigues me as we see characters obviously painted as good or bad based on more traditional morality foundations. In the latest episode, The Suicide King, newly introduced characters Adam and Ben argue with Tyreese and Sasha that they should overpower Rick’s group. They essentially argue that with the veneer of civilization gone and it’s survival of the fittest. (We’re also supposed to believe the Governor of Woodbury is “wicked” because his team kills others and takes their supplies for their town of folks.) However, Tyreese later tells an untrusting Rick that turning his small group away – sending them out from the prison instead of letting them share – is basically a death sentence in its own right. While he doesn’t call it a “sin of omission”, it’s still a decision that decisively chooses one group’s survival over others.

Writer/creator Robert Kirkman (who works on both the comic and television show) professes to be an atheist, and while the book has shown supporting characters discuss God and religion, it isn’t central to protagonist Rick Grimes, or the main thrust of characters and their decision-making. This is understandable, but intrigues me as we see characters obviously painted as good or bad based on more traditional morality foundations. In the latest episode, The Suicide King, newly introduced characters Adam and Ben argue with Tyreese and Sasha that they should overpower Rick’s group. They essentially argue that with the veneer of civilization gone and it’s survival of the fittest. (We’re also supposed to believe the Governor of Woodbury is “wicked” because his team kills others and takes their supplies for their town of folks.) However, Tyreese later tells an untrusting Rick that turning his small group away – sending them out from the prison instead of letting them share – is basically a death sentence in its own right. While he doesn’t call it a “sin of omission”, it’s still a decision that decisively chooses one group’s survival over others.

In the comic book, Rick’s morality and the Governor’s are – quite literally – more black and white. The choice of the television show might reflect a more Nietzschean, “God-is-dead” nihilism where moral values are abstractly contrived. However, there is still a sense to the viewer that Tyreese is “right” and virtuous, that his friends Adam and Ben are “wrong”. From Romero’s groundbreaking zombie films to The Walking Dead, there seems to be a fear that the collapse of civilization will reduce us to animals (or the zombies themselves) simply consuming for our own continuance at the expense of or disregard of others, salmon swimming desperately upstream jumping over each other to spawn and perpetuate ourselves however we can.

In the comic book, Rick’s morality and the Governor’s are – quite literally – more black and white. The choice of the television show might reflect a more Nietzschean, “God-is-dead” nihilism where moral values are abstractly contrived. However, there is still a sense to the viewer that Tyreese is “right” and virtuous, that his friends Adam and Ben are “wrong”. From Romero’s groundbreaking zombie films to The Walking Dead, there seems to be a fear that the collapse of civilization will reduce us to animals (or the zombies themselves) simply consuming for our own continuance at the expense of or disregard of others, salmon swimming desperately upstream jumping over each other to spawn and perpetuate ourselves however we can.

However, if we believe we’re effectively nothing more than animals anyway – no God, no objective morality, no true evil – then how is this really being reduced in any true sense? It’s just accepting what we are and being honest. We then lose all ability to judge the governor, or Rick, or even the great we-love-to-hate Merle Dixon. One could argue men like Tyreese, Hershel and others are simply operating out of enculturated systems of thought linked to “archaic religious notions” that we’re image-bearers, that we were born to imitate something nobler than survival of the fittest, to reflect the heart of our Creator. In second season, Shane argued these notions should be cast aside… that in the new world order, such concepts only hurt the group and get people killed.

If I were an atheist, I’m not sure I could root for this narrative’s protagonist and be consistent with my worldview.

If I were an atheist, I’m not sure I could root for this narrative’s protagonist and be consistent with my worldview.

Another thing that seems clear about the show, be it protagonist or antagonist, is the idea that people need a single leader to follow, particularly in a time of crisis. Attempts at democracy and voting fail and by the end of season two Rick declares himself the boss and we have what fans have called a “Ricktatorship”. From the Roman role of the dictator to Marvel’s Latverian monarch Victor Von Doom, to the Christian view that the best form of government is truly a benevolent dictatorship (Christ), this need for singular authority and followers on every side of The Walking Dead’s survivor groups creates another intriguing window for conversation. On top of that, the failure of ANY of these men to lead effectively long term adds another element, in that perhaps this need can never fully be met by a human, that they will ultimately fail (by abusing their power, or perhaps being haunted by the ghost of their dead spouse).

The comic has seen far more horrors, and far more “seasons” go by for the characters, and many faces in the television show are no longer with us in the comic story. While I obviously have my opinions about the fluctuating quality of the television show, even the comic – after 100 issues – is losing some of its luster for me. Since I can’t speak into the lives of these characters, express the hope that I have, their reasons for living and their inevitable fate are starting to feel tiresome, lamentable. A friend said he stopped reading the comic because the story, as he put it, “contains absolutely no hope.”

The comic has seen far more horrors, and far more “seasons” go by for the characters, and many faces in the television show are no longer with us in the comic story. While I obviously have my opinions about the fluctuating quality of the television show, even the comic – after 100 issues – is losing some of its luster for me. Since I can’t speak into the lives of these characters, express the hope that I have, their reasons for living and their inevitable fate are starting to feel tiresome, lamentable. A friend said he stopped reading the comic because the story, as he put it, “contains absolutely no hope.”

The journey of Rick and Carl remind me of Cormac McCarthy’s traveling father and son in The Road. In the book, the father keeps telling his son that they are the “good guys” and that they are “carrying the fire”. However, in The Walking Dead it’s not clear there is anything we can call objectively good, and whether there is truly any fire worth being preserved.

What fire, or true light, should we be carrying beyond mere survival?

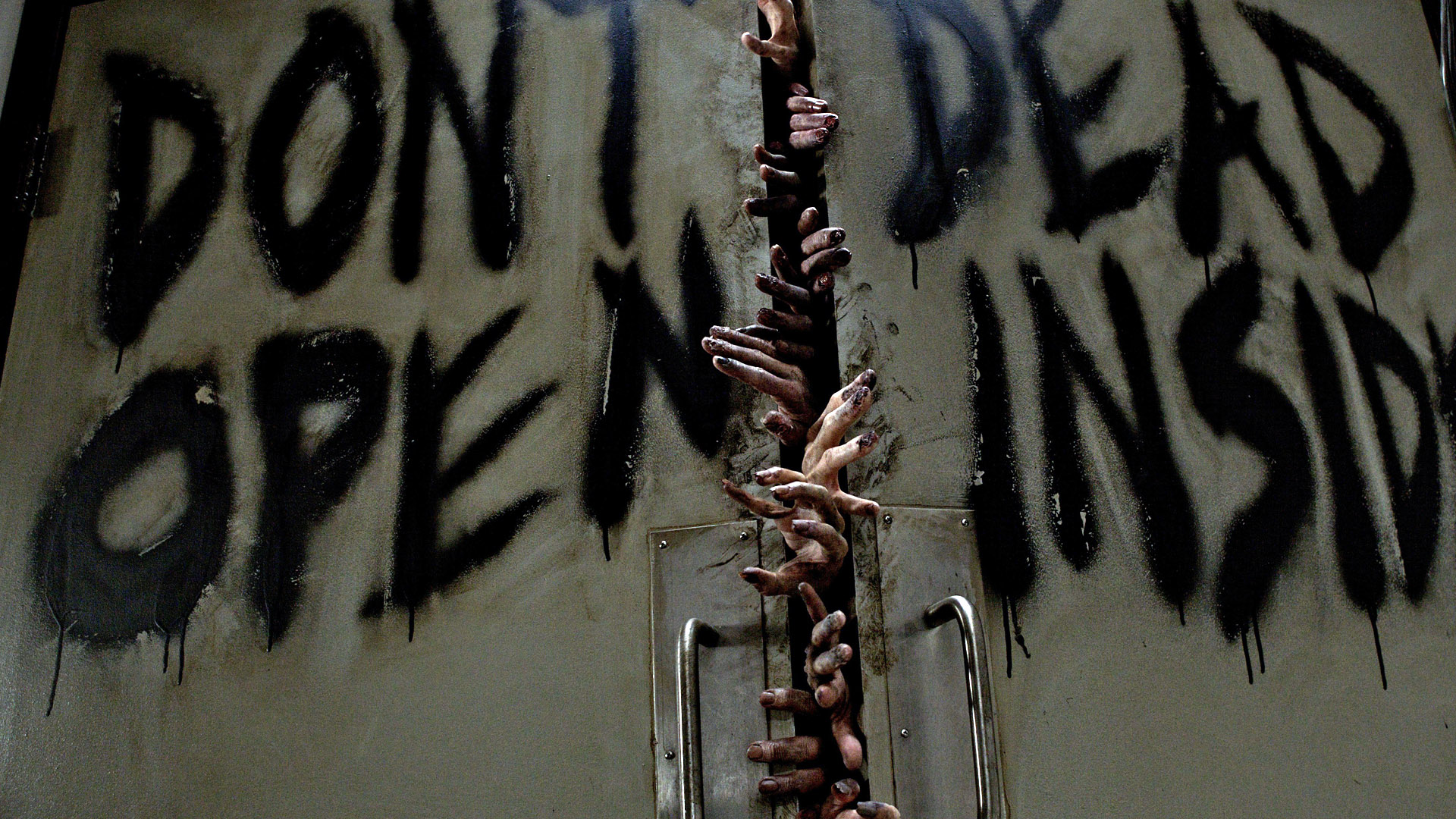

By peeling back the myriad layers of comfort and distraction we have in the 21st century, and painting all of life as an ever-crawling death nipping inevitably at our heels (and legs, arms, torso and brains) The Walking Dead resurrects age-old questions of why we keep moving through life, what reasons we have to perpetuate our existence, why we hold onto the moral values we live by, and what – if any – true hope we have. Many of us shamble through life like walkers, not bothering to question these things, and sometimes we need a series like this to stop us dead in our tracks: to make us think about whether we’re even truly living.

I read the comic up to the end of the prison story-arc and watched the TV show up to the death of Lorrie.

I couldn’t watch or read anymore. I have the same basic problem with both – they are both well written, especially the comic which is a page-turner, but it’s too dark. There are no heroes in the traditional sense and that’s depressing.

It’s the same issue of why I abandoned the Game of Throne books and TV show. There are no heroes.

[…] Bringing The Walking Dead to Life at Cinemagogue […]