A review of “FIGHT CLUB”

by James Harleman

Starring

Brad Pitt

Edward Norton

Helena Bonham Carter

Directed by David Fincher

Based on the book by Chuck Palahniuk

139 minutes, Rated R

Tyler Durden is right…

For those who’ve already seen “Fight Club”, (the latest cinematic offering from the man who brought us the horrific mystery “Seven” and the debatably good thriller “The Game”) the above assessment may greatly disturb them. But bear with me… because it’s true.

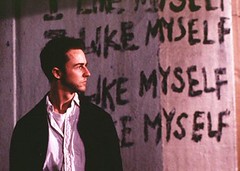

In this film, an insomniac narrator and central figure (played with incredible energy by Edward Norton) ushers us into Director David Fincher’s expose’ on the great lie we call the American Dream. In “Fight Club”, we find a man chafing at his own sheep-like adherence to the rampant consumerism and mandates of a detached, cardboard-cut-out society. He blames his inability to sleep on this sterile and lifeless environment, and, when denied medication for his condition, seeks to fill the void by more unconventional means.

The film offers a brutally truthful look at “self-help” groups and emotional therapy sessions, exposing them as, though perhaps a healthier outlet or focus for those with afflictions, ultimately just another form of addiction… a mass-medicating illusion to help ignore the pain and inevitable truth of one’s condition. They offer no kind of lasting hope. As Norton’s haggard character floats through these huddled, pitiful masses, feigning their conditions so he might commiserate over their “shared” problems, it becomes obvious that these are just more band-aids on the bullet-wounds, a way to cover and mask pain without finding any solution to the problems. Feeling their pain, and fleeting taste of redemption, he finds he is able to sleep… for a while. Inevitably, another character enters the film and this “connection” is severed.

The pivotal moment of the narrative arrives when this desk-riding insurance investigator loses his condo and possessions in a bizarre incident; with nowhere else to go, he runs headlong into the enigmatic Tyler Durden: purveyor of home-made soap, part-time waiter at an upscale restaurant, theater projectionist, and dispenser of very simple and honest wisdom.

“You are not your job! You are not your bank account!”

“The things you own end up owning you.”

“We were raised to believe we would all be millionaires, rock stars, and movie gods… but we won’t.”

Spurred on by Tyler’s reckless yet honest ideology (and a drunken fight), the two realize that, in this insulated society, pain is at least one way to actually FEEL something (to feel alive) and hence is born the Fight Club – a violent outlet for taking back the reins of their own lives, a filthy basement arena where an ever-increasing number of blue-collar men violently vent their inner demons on one another. The experience empowers our passive protagonist on the job, making him dangerously assertive. His fears dissolve one by one, as does his reliance on social norms and material goods.

Growing numbers of men, freed from convention and led by the alpha-dominant Tyler Durden, eventually take the fights out of the basement and into the streets. Vandalism, social statements and finally an explosive “master plan” – to upend the white-collar ruling class – take two men’s shared realization about the world to unbelievable extremes. The Fight Club has evolved into a movement, a regime, a social order and secret society, literally embodying Nietzsche’s concept of will-to-power with Tyler as its backstreet Stalin. Though Edward Norton’s impressionable character begins to balk and back-peddle as things spiral out of control, he ultimately finds there is more of Tyler Durden’s mindset in him than he realized.

“Congratulations-you just had a near-life experience.”

Many critics will say the film’s message is about the modern male’s fear of losing power in society, but this analysis merely only scratches the surface. In the postmodern landscape, where people have become disenchanted with sound-bite promises of utopia, the gospel of Tyler Durden makes a lot of sense. Materialism is indeed fruitless, while social conformity and corporate ladders lead nowhere. The American “pursuit of happiness” is like a running through the Winchester Mansion; half the doors promise great rooms beyond, but don’t open, and stairways go nowhere, except perhaps to a deadly precipice. In the film, our narrator nests his house with Ikea’s best furnishings and updates his wardrobe, but why? It all turns to dust. As Solomon reminds us in Ecclesiastes – it’s meaningless, it’s vanity, and it fades.

-

Tyler Durden speaks a lot of truth… in his assessment of the world.

-

The only thing wrong is his solution.

Like Nietzsche’s madman, wondering why (if God is dead) man still clings to soft, archaic, religion-inspired morals, “Fight Club’s” Tyler Durden takes pure, atheist reasoning to its logical conclusion. Though simultaneously appalling, it’s refreshing to see someone who – in rejecting God – lives out their worldview consistently. No God; no consequences; no objective morality. No one but me to define my morality; I define the world as I see it. My will makes me right; my might makes right… or in this case, the Fight Club makes right.

Like Nietzsche’s madman, wondering why (if God is dead) man still clings to soft, archaic, religion-inspired morals, “Fight Club’s” Tyler Durden takes pure, atheist reasoning to its logical conclusion. Though simultaneously appalling, it’s refreshing to see someone who – in rejecting God – lives out their worldview consistently. No God; no consequences; no objective morality. No one but me to define my morality; I define the world as I see it. My will makes me right; my might makes right… or in this case, the Fight Club makes right.

Quite honestly, if I didn’t believe in God, I would join Tyler Durden in his philosophy. If God didn’t exist – if Christ didn’t offer salvation – then Tyler would be right… and to live otherwise in this mad world would be hypocritical, and a waste of air.

“Fathers model God to their kids… if our Fathers failed, what does that tell us about God? He doesn’t like you… he doesn’t care about you…”

Tyler’s error is that he sees an imperfect model, then jumps to the conclusion that what it sought to model is equally flawed; however, just because a mirror is broken, that doesn’t mean what it’s reflecting has cracks in it. He’s made the same mistake many people do when they judge God solely by a flawed, imperfect Christian who has stumbled while trying to model their Savior. Also – in Tyler and his protege’s case – too many of their generation’s fathers never even tried to model Jesus to their children. Their reaction and rejection of this often-mismanaged, baby-boomer parentage is not surprising.

Although both Norton’s narrator and Tyler Durden recognize the sickness and hypocrisy in the world (a common theme in Fincher’s films) they still rely on themselves – on men – to fix it. Norton’s evolving character discovers this doesn’t work, because he, like the world, is equally flawed. Tyler instructs Norton’s weak-willed self that he must “hit bottom” before he can truly live… and again, he is half-right. Everyone needs to hit bottom – to acknowledge the shortcomings of society, culture, and most especially themselves – and to stop diluting and/or ignoring their pain and helpless condition. However, no one may rise – or be born again – by their own will or power.

-

That’s the point – we don’t cure, medicate, or repair our broken selves.

-

We rely on Christ, and His perfection, and His redemption; that’s the only way we can truly live.

Brad Pitt delivers a raw, edgy performance, recapturing some of the Indie-quality he’d lost to his more recent, mainstream, pretty-boy image. Ed Norton is, as always, in top form, and the nervous, jittery role seems to play to his strengths. Helena Bonham Carter, who plays the depressive, neurotic and slightly suicidal woman who becomes entangled with both Norton’s POV figure and Tyler, is brilliant and edgy as Marla. As with many of her onscreen characters, she brings a strange, hybrid quality-of jaded adult and petulant child-to her role, both in personality and appearance. Fincher brings out the best-or worst, when he wants to-in his actors. Indeed, Pitt hasn’t shined this brightly since “Seven”.

“Fight Club” contains excessive graphic violence, a lot of blood, and a considerable amount of profanity. It is not for the timid, or those with a conscience issue. Still, I would highly recommend the film; the acting is superb, the cinematography is riveting, and it’s sociological content, (and subsequent theological implications) might make for fascinating and challenging discussions with non-believers. There are sexual situations and some brief, flash-frames of nudity, (though not nearly as explicit as say, “The Devil’s Advocate”, a film I also highly recommend).

I personally found David Fincher’s “The Game” to be lacking, but with “Fight Club”, Fincher is back in top form. Fincher’s dark, potent visions paint a nihilistic portrait of a broken world that offers no hope. These can serve as both a reminder to, and a springboard for, the Christian – who desires to bring our hope in Christ to the broken society we live in.

[…] 3. Fight Club A scathing critique of modern culture, covering everything from materialism, to men robbed of masculinity, to the shortcomings of self-help therapy, to the ultimate “logic†of Nietzchean will-to-power apart from Christ. All this and black comedy. (R) For a full review, click here. […]

[…] the enigmatic revolutionary figure played by Brad Pitt in the David Fincher directed Fight Club, beat out the Godfather, Han Solo and even Darth Vader for the top spot. Not bad for a film with […]

[…] “Our fathers were our models for God. If our fathers failed, what does that tell you about God?” – Tyler Durden, Fight Club […]

[…] To read Cinemagogue’s original punch from our 1999 review of Fight Club, I want you to click this as hard as you can. […]

I just realized how much FIGHT CLUB changed my life!

Excellent review, brother; one of the best I have read on this theologically rich film (and I have read a LOT)!! Kudos and blessings.