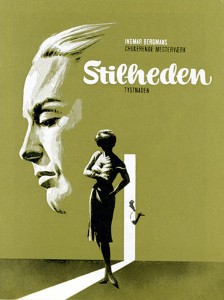

(No, this isn’t about alien villains from Doctor Who. It IS a great examination of the 1963 Bergman film by guest reviewer Rob Martin!)

(No, this isn’t about alien villains from Doctor Who. It IS a great examination of the 1963 Bergman film by guest reviewer Rob Martin!)

As she travels home by way of train, terminally ill Ester, along with her sister Anna and nephew Johan, takes a rest in imagined Timoka, a Central European town draped in the shadow of impending war. Such is the canvas for Ingmar Bergman’s almost silent, ninety-six minute existential exploration of a fractured sibling relationship, a relationship in which any hope of final reconciliation is threatened by Ester’s certain demise.

The third film in Bergman’s “Trilogy of Faith,” The Silence concerns the purpose of life in a universe where God is silent, either through indifference or nonexistence. It’s a reality where, despite our best efforts to find purpose in either work or a pursuit of pleasure, we ultimately face the inevitable silence… which communicates to us that we are absolutely alone. We live short lives in which we must come to terms with the unfortunate pessimism that one day all of our achievements will be buried beneath the chaos a cold, hostile universe. We are not loved. We are without hope of rescue and nobody is coming to rescue us from the dark despair of death that each of us faces alone.

God is Dead. There is only Silence.

Cultural anthropologists describe the pre-modern era as one in which a person found their sense of self and purpose in the supernatural world. This era was followed by the modern period, an age of great optimism in the human spirit, marked by an immense growth in both science and technology, as well as a seeming understanding of how the natural world was ordered. Man was thus departing from the primitive savagery of superstition, as human achievement would ring in a golden age of reason. However, the utopic vision of the modern age was shattered as its technological advancements rather ushered in the beginnings of dystopia. Man now had the ability to instantly level cities and kill multitudes at the press of a button. Thus, after two world wars, the optimism of modernity descended into the pessimism of postmodernity. Not only was God dead, but there is no way to truly know what is truth.

Cultural anthropologists describe the pre-modern era as one in which a person found their sense of self and purpose in the supernatural world. This era was followed by the modern period, an age of great optimism in the human spirit, marked by an immense growth in both science and technology, as well as a seeming understanding of how the natural world was ordered. Man was thus departing from the primitive savagery of superstition, as human achievement would ring in a golden age of reason. However, the utopic vision of the modern age was shattered as its technological advancements rather ushered in the beginnings of dystopia. Man now had the ability to instantly level cities and kill multitudes at the press of a button. Thus, after two world wars, the optimism of modernity descended into the pessimism of postmodernity. Not only was God dead, but there is no way to truly know what is truth.

We are left without meaning. There is only silence.

To convey this idea, Berman employed minimal dialogue and placed such alongside the unintelligible language of Timoka, which Ester (a professional translator) could not even decipher. Johan speaks the film’s first words, as he reads a sign written in this made-up language: Nitsel Stantnjon Palik.

“What does that mean?” He asks his aunt.

“I don’t know.” She responds.

If these words have meaning, it cannot be discovered. They simply exist without communicating anything. The only meaning that one can find in a chaotic, lonely universe is in the very act of living itself. Such was Bergman’s worldview, as evident in his autobiography, The Magic Lantern: “You were born without purpose, you live without meaning, living is its own meaning.”

If these words have meaning, it cannot be discovered. They simply exist without communicating anything. The only meaning that one can find in a chaotic, lonely universe is in the very act of living itself. Such was Bergman’s worldview, as evident in his autobiography, The Magic Lantern: “You were born without purpose, you live without meaning, living is its own meaning.”

Thus, we fill the fill the silence to dampen its maddening effects, as we make the most out of our time here under the sun.

The Pathos of King Solomon

In contrast to Timoka’s unintelligible language, and the utter despair of a meaningless universe, beauty still exists. To illustrate this, Bergman fills some of the silence of The Silence with Bach’s “Goldberg Variations.” Regarding this, Francis Schaeffer writes of an interview in which Bergman expounded on this theme—that within the human framework there is a holy part to which music speaks.

Bergman rightly understands that humans were made to communicate, to be relational, to have meaning and purpose. He simply was unable to truly live with his existential position, as Schaeffer points out. Thus, we see Ester finding solace through Bach within her gradual decay. She comments to the old man who tends her hotel room on the universality of music. Even though they did not understand one other, they both understood Bach. They could both experience it in the same way.

Anna, rather than filling the silence with sophistication, connects through promiscuity. After sleeping with a waiter she met in a café she tells him that even though they do not speak the same language, they are still able to enjoy one another and be silent. “It’s wonderful,”she asserts. In another emotional scene, Anna ridicules Ester, insisting that she complicates life.

Anna, rather than filling the silence with sophistication, connects through promiscuity. After sleeping with a waiter she met in a café she tells him that even though they do not speak the same language, they are still able to enjoy one another and be silent. “It’s wonderful,”she asserts. In another emotional scene, Anna ridicules Ester, insisting that she complicates life.

Anna: “…you always harp on your principles… Everything has to be desperately important and meaningful…”

Ester: “How else can one live?”

Anna believes that her sister is afraid of her because she can find peace in her loose living, in accepting the silence and embracing the despair of the universe.

King Solomon experienced a similar existential crisis at the end of his life. He had turned from God and drove headlong into the silence to see if he could find meaning apart Him. After searching in a multitude of areas, money, political power, sex, the arts and sciences, he determined that “all is vanity, or a vapor” (Ecclesiastes 1:2ff). If our whole purpose is living, which is only temporal, and our life is but a vapor that is here one day and gone the next; if we are to simply live, die and be forgotten, life is a certainly a meaningless masquerade. Thus, Solomon reminds us to remember our Creator before such a time (12:1-8).

God Has Broken The Silence

God Has Broken The Silence

Hebrews 1:1-2 teaches us that “Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son.” This Son was the divine logos, the Word that became flesh and dwelt among us (John 1:14). In the incarnation, the Son added humanity to Himself and thus became the bridge between the material and spiritual world. Christ is the “exact imprint” of the Father (Heb. 1:3). In this verse, the Greek word behind “exact imprint” refers to the impress on a seal. The idea being that, when the seal is pressed onto wax, the wax bears the same image as the seal.

When we view Christ, we view the very nature of the Father who has “broken the silence”, demonstrating His love for us in the atoning work of the Son on the Cross. What is fascinating is that the only time that God was truly silent was at the cross, as He turned His face from His Son who became sin on our behalf (Matt. 27:46; 2 Cor. 5:21).

It is emotionally jarring to see the characters in Bergman’s film wrestling with such uncertainty, and we may all have been in similar position at one time. Thank God when the credits roll on that story, we can know in our story that:

-

We are loved.

-

We are not without hope.

-

There is rescue from the silence.